The (Re)Search for Inclusive Healthcare

- Global Health

- Social Justice

In partnership with Cedars-Sinai Research Center for Health Equity, this Fall 2022 Designmatters studio challenged ArtCenter students to explore the current lack of diverse representation in clinical trials. By designing an inviting digital and print awareness campaign, Los Angeles Latino and Korean community members would possibly consider participating in clinical trials; likewise healthcare providers, who often are subject to racial biases, would consider inviting members of these ethnic communities to become involved in potentially life-saving cancer treatments.

Students created strong messaging, resource material, language and cultural identity collateral along with distribution systems that focus on community members and leaders, healthcare practitioners, clinical staff, primary care physicians and advocates. Understanding the barriers involved in engaging these audiences, students crafted campaign resources and toolkits that cemented the overall importance of taking part in clinical trials that could save lives.

“I was a physical therapy major before coming to ArtCenter and always have been interested in the medical field. This studio provided real-world opportunities to learn what we can do as designers and artists to help others.”

– Jesslyn Lee (Fine Art)

Project Brief

Transdisciplinary ArtCenter students researched the lack of diversity in life-saving clinical trials and designed an effective awareness campaign that would dispel fears and encourage participation of local Latino and Korean communities that are underrepresented in these trials as well as encourage health practitioners to invite these ethnic groups to joining a clinical trial.

Working with partner Cedars-Sinai Research Center for Health Equity, students first investigated the barriers that have hindered community members from participating or health practitioners from inviting. Informed by their research, student teams designed campaigns with strong positive messaging and innovative strategies that support wider diversity participation in clinical trials, targeting community members as well as healthcare providers.

“The students really thought about the whole system in which people get care –and looked at the issues from the neighborhood, the church, [and] the clinic to the cancer center to the community of cancer patients and survivors. I think that looking at the issue comprehensively, designing specific products and materials for each target audience brings it all together for us.”

– Zulfikarali Surani (Cedars Sinai Research Center for Health Equity)

About Clinical Trials

As the heart of modern medical research, clinical trials provide scientists with vital real-life data that can help prevent, detect and treat diseases – but these experimental trials historically have had an identity crisis: participants are overwhelmingly white and male.

According to a recently published Tufts University study, 76 percent of clinical trial participants from 2007 to 2017 are Caucasian.

Many community members are hesitant to engage in such studies because of the industry’s past abuses of the program, citing especially the Tuskegee Study which allowed Black Male participants to suffer and die from untreated syphilis. Additionally, racial bias in the medical community means that many health care providers don’t even suggest clinical trials to their patients of color.

Today, the industry understands the importance of having participants from a variety of backgrounds and ethnic groups when testing the effectiveness of drugs, procedures and treatments. The benefits of having diverse participation in clinical trials can offer possible life-saving solutions especially for non-Caucasian communities.

Research and Project Development

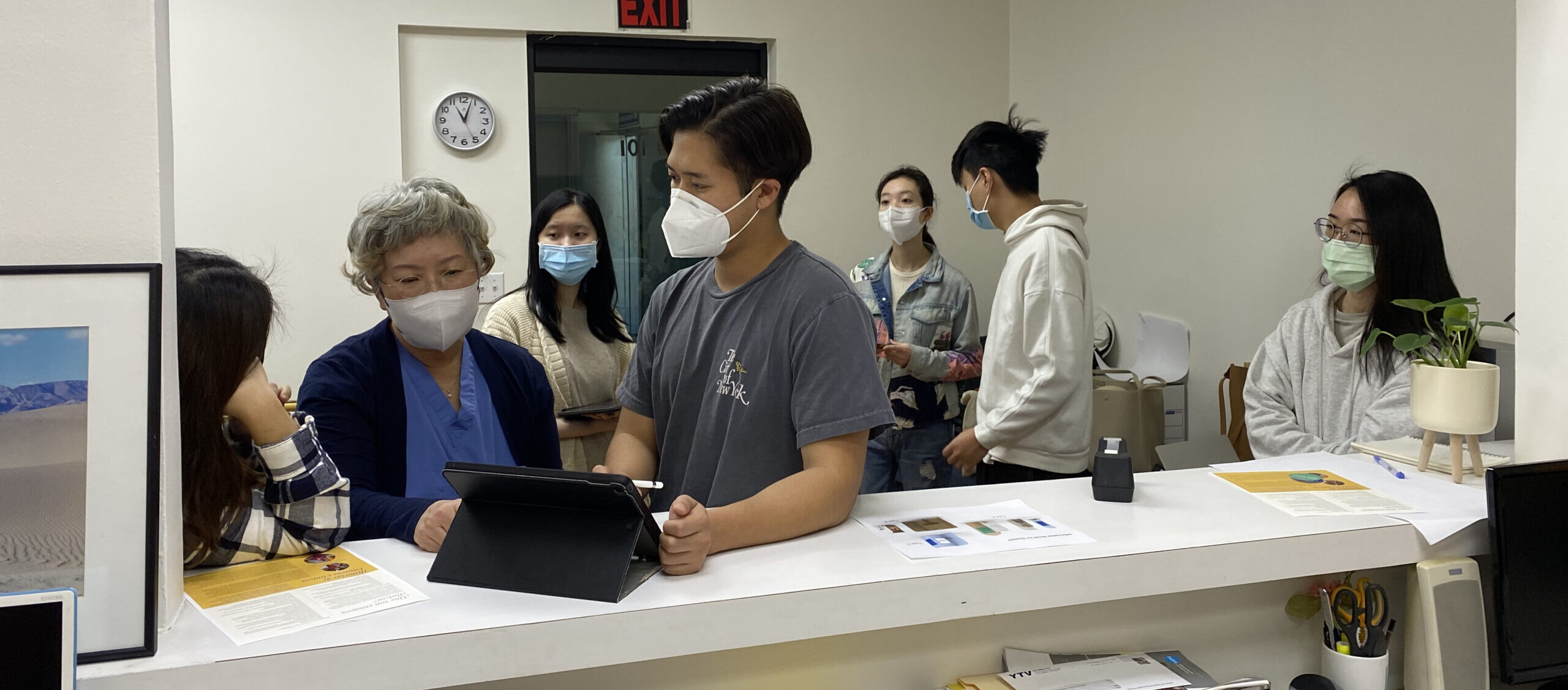

At the kick-off session, students met key players from Cedars Sinai who will be advising and co-creating with them during the course of the studio.

Students heard an overview of the work of Cedar Sinai Research Center for Health Equality and how, through various methods, they have built trust with certain marginalized and underserved communities. Often this trust is created by one-on-one contacts where people live, work and play. “Our outreach is focused at a neighborhood level,” says Zulfikarali Surani, Director of Community Outreach and Engagement.

For example, Cedar’s Promotoras program – where bilingual individuals meet regularly with residents – has been successfully connecting one-on-one with Latino populations to discuss better health practices, vaccinations, etc.

Encouraging more clinical trial participation from underserved communities – especially Latinx and Asian American – is the next big challenge for the Cedars team. A discussion of the value of clinical trials enlightened students to the dilemma faced by health researchers. Clinical trials invite human participants to be involved in medical advancements in drugs, devices and treatment methods –especially needed in order to treat debilitating cancers.

“I love the stuff we designers can do here in school, but sometimes it feels like we are in an academic bubble. This is the first group project I’ve had at ArtCenter. This was a whole exercise of working with other disciplines, different ages. While this studio was an experience of working in groups, it was also an experience of listening. Really trying to be as unbiased as you can and place yourself outside of yourself.”

– Noah Cousineau (Graduate Graphic Design)

Right now, the medical community is struggling to address the racial inequalities that exist in clinical trials; mostly older white men have been participating. Minority populations are severely underrepresented, which can be problematic for some groups that experience certain cancers more than others.

Potential participants typically first hear about a clinical trial from their healthcare provider. Sometimes, however, there is racial bias that keeps providers from sharing information with their patients.

However, educating health care providers is only one avenue to raise awareness and increase participation. If awareness can also be created within the community, members could insist their doctors or health care providers connect them to relevant trials.

To craft any kind of awareness campaign, clear communication is necessary, according to the Cedars team. Students were encouraged by Cedars to avoid technical terms, but rather explain benefits and risks in simple language. Cultural sensitivity is also needed. In many cultures, a major healthcare decision is a family decision. Ultimately, to narrow down the Asian-American data segment, students and Cedars-Sinai decoded to focus on the local Korean community in Los Angeles in addition to specific Latinx neighborhoods.

Students requested additional data about how trials are administrated by Cedars. Students learned about online resources from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) which provided additional statistics and details about clinical trials.

The Cedars team described some barriers that they have encountered from residents, as to why they didn’t want to participate in clinical trials. Residents stated:

- Insufficient education about that a clinical trial is

- Doctors seemed unaware of residents demographic and culture

- Not sure how to find a trial

- Clinical trial providers are unwelcoming

In addition Cedars presented some responses when trials were offered but rejected by residents. Some reasons expressed were:

- A perceived harm to the resident

- A Mistrust of what informed consent means

- The cost to the resident (transportation, finding child care, etc.)

- Resident fears that clinical trial means they are being “experimented on”

Conversely, the Cedars team shared what methods have been working, pointing to how doctor referrals are effective along with:

- Recruitment in a community setting that clears hurdles of participation, i.e., language and transportation

- An involved community voice

- Culturally appropriate materials, visuals, etc.

- Social media

- Incentives

For example, they described how the waiting room is the perfect place for community health workers and patient navigators to discuss clinical trials. Another good forum is public screenings at health fairs. Finally, students were encouraged to investigate locations where community members work, play and worship.

As the kick-off meeting concluded, students and Cedars members created a list of attributes often associated with a successful campaign. These attributes would help guide student thinking about various approaches.

- The Campaign “must include”: ______

- The Campaign “should include”: _______

- The Campaign “could include”: _______

- The Campaign “will not include”: ______

Both students and Cedars team members left with an eagerness to move the concept forward. Students were excited to use their talents in a real-world challenge that could ultimately make a difference.

“[The] concept of warmth in our campaign was with us from day one – but our definition of what warmth was changed over time.”

– Noah Cousineau (Graduate Graphic Design)

Research with an Empathic Approach

In the first weeks of the studio, teams participated in active research as they were introduced to human-centered design (HCD), which would fuel their research and design-thinking.

The students learned that HCD involves seeing their intended audience through empathic eyes. Through active listening, students can see layers involved in the audience’s challenging pain points. Personal experiences relayed by community members often reveal important insights that can direct designers to thoughtful solutions.

Students gathered statistics about clinical trials, noting the diversity gap. They also delved into the local Latinx and Korean communities by traveling in-person to hub locations – such as churches and clinics – to immerse themselves into their culture.

Throughout the studio students were fortunate to hear from and interview a variety of presenters and living experts. Teams listened to longtime nurse and cancer patient/survivor Linda Pura discuss her journey being in a clinical trial, especially the pitfalls that occurred and how those difficulties could be rectified.

Another presenter, Dr. Ghecemy Lopez, shared her triple negative breast cancer story from diagnosis through treatments to being cancer-free. Because of this life-changing experience, she became a lay patient navigator at USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, assisting others with issues of housing, finances and transportation as well as being an interpreter during doctor appointments.

Teams audited other campaigns to examine how their graphics, text and tone presented a distinct concept and approach. What worked? What didn’t? What design lessons can be learned from this campaign?

After only five weeks of investigations, students presented a research/insight review with the Cedars team as well as what they viewed as four main challenges to focus on: (1) an element that informed them the most, (2) an intended audience, (3) campaign direction #1, and (4) Campaign direction #2.

The feedback from the Cedars team was necessary as it would help propel the students forward. Which opportunity is the most promising? What seems the most exciting? And how do the students’ insights differ from Cedars’ team experiences with clinical trials?

“Our partnership with Cedars, the way that they presented different guests to come into the studio and opportunities to visit clinics and churches was very pivotal in the students’ understanding of where this work would be seen and utilized in the community. At the end of each class, I had a to-do list from the students who really pushed for these interactions. They really wanted to have as much connection, not only with the Cedars team but also with doctors, patients, community members to validate that their ideas were on the right track. They

were able to make a lot of great refinements to their concepts because of these experiences.”

– Monica Schlaug (Faculty)

The Cedars team was impressed with how the students conducted their research, the data they collected, and the information gathered from other comparable campaigns. Cedars team members often riffed with one another on ideas and possibilities, which excited the students.

Students asked for clarification on certain comments, inquired about other elements of the health care system (“Where do former patients come together?”) and asked for introductions into the communities (i.e. churches, community centers, leaders, etc.) along with additional resources for connection.

Overall, the feedback gave new insights to the students as they reexamined how their concepts could be measured for success. They pondered: How could their ideas be scalable? Which one would be the easiest to implement?

With only a few weeks to refine their concept for midterm presentation, teams were also challenged to create a new Problem Statement and craft HMW (How May We) statements.

Students dug deeper into how their concept would achieve all the impactful touchpoints, and along the way, carefully inspecting how each step would contribute to the keywords they chose to define their project. Teams developed a campaign “brand essence” and designed user personas that would hypothetically engage in the campaign.

As they were creating, teams constantly circled back to recollecting the personal stories they heard of people diagnosed with cancer. Keeping those individuals – and their health care team – in mind helped ground their work in reality.

“Although these projects take a singular approach to the White Sage Campaign, they are interconnected and help advance one another.”

Joel Garcia (Huichol), instructor

During midterms, teams recapped their research and presented one initial concept, defined deliverable components, and shared a campaign logo that encompassed their concept.

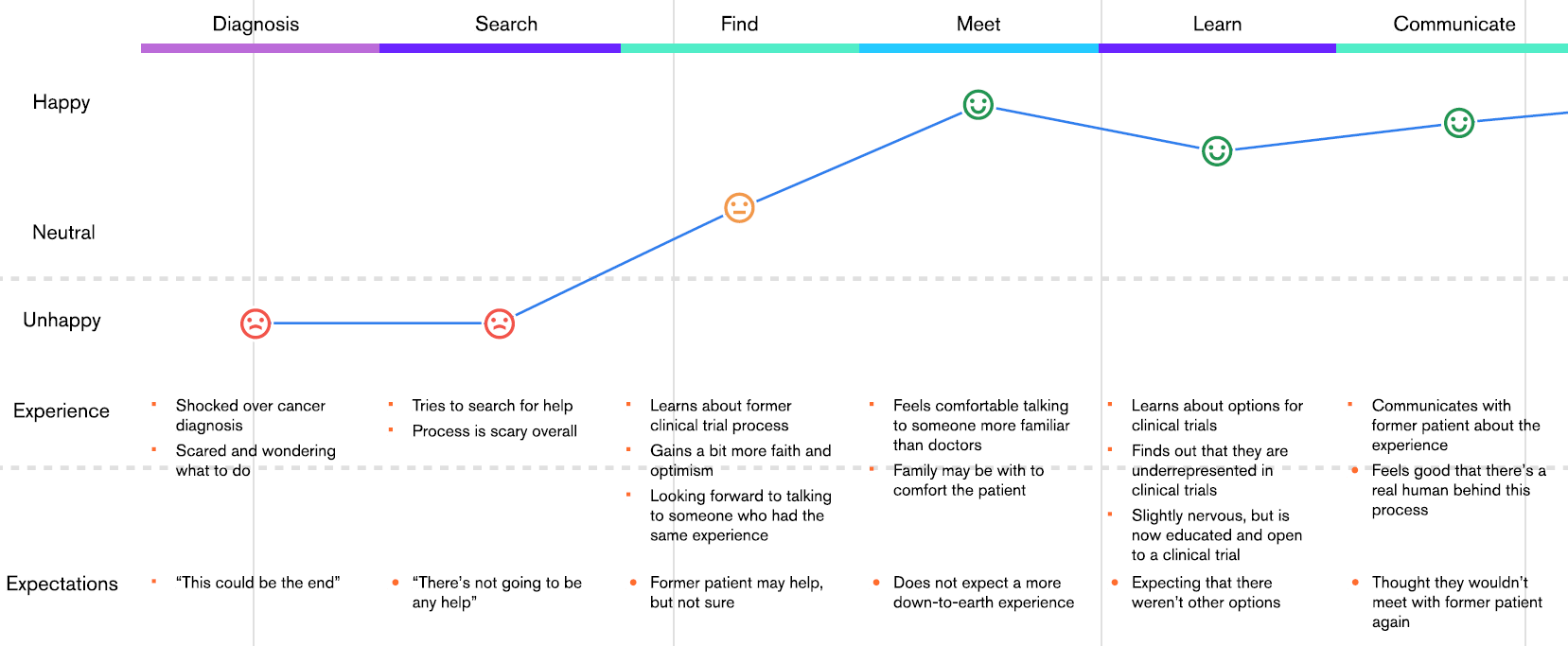

Through User Journeys, teams demonstrated how this campaign would actively engage a specific target audience. Interestingly, each team focused on a different audience for their campaign.

Mood boards offered details on a color system, graphics, typography, illustration/photo style and iconography that would accompany their campaign. Finally, teams developed a plan to move forward from this presentation, such as developing a prototype of their product/system.

Again, Cedars feedback was thought-provoking for students. They discussed possible adjustments and pointed out certain health regulations – such as privacy concerns – that needed to be considered. They reminded students to make sure they have one clear, distinct message – too many can be messy and confusing.

Armed with comments and suggestions, student teams moved into a refinement phase to brand their concept with final imagery and text. Since their campaigns would be directed to Latinx and Korean audiences, Cedars partners were enlisted to help with translations, especially text within posters, brochures and other print materials.

Final elements were added to digital components that complemented the campaign.

“This project was so much branding. There was the web platform, physical elements and graphic design and promo items. The overall fidelity of the project was very important to us – not only for our portfolios but more so, to our sponsors who were our partners in this studio.”

– Lillian Yian Lin (Product Design)

Final Outcomes

close

close

Be a Part of the Cure for the Community

Read moreXiyu Chen, Jesslyn Lee, Megan Pantiskas

Focusing on older adults in Latinx and Korean communities, this campaign offers basic information about clinical trials and positive participation

experiences to encourage others to join an appropriate trial.

Print elements will be placed in out-of-home spaces such as bus stops, churches, retirement centers, etc. (including events at those locations). Posters depict colorful illustrations of multicultural people accompanied by short but informational text. A six-panel folded brochure highlights a personal story along with Frequently Asked Questions. Type is professional yet friendly and is easy to read in various languages.

The campaign’s circular logo combines handwritten text in the center with a professional font for outside curves. Logo stickers can be handed out at in-person events, health fairs, etc.

The color palette for the logo and other elements change according to the community language. Illustrations are simple line drawings with bright, eye-catching colors. Iconographic images are designed for quick understanding.

The Social media look will incorporate design elements from the print campaign, as well as on the dedicated campaign website. The website will connect directly to Cedars Sinai’s webpage.

close

close

DiverCT

Read moreCindy Chu, Taiga Haruyama, Lillian Yian Lin

To empower health care providers to be a source of information about clinical trials for their patients, this campaign supports oncologists, nurse/patient navigators and primary care physicians. A website features up-to-date clinical trial news and a community guide to help medical staff understand the specific cultural needs of their patients.

The campaign logo reflects the merging of diversity and professionalism. The Din Diver is a rainbow of colors while the CT is approachable and straightforward.

Displayed in healthcare settings, posters will engage the healthcare community as well as patients. For medical staff, posters announce “Healthcare Providers are Information Providers” with engaging sentences and a QR code for more information. Staff can wear pins with the slogans: “Ask me about clinical trials,” and “Clinical trials provide hope.”

For patients, posters describe the benefits of clinical trials and feature photo imagery tailored to ethnic communities. Smaller versions become flyers with additional information.

Printed items can be displayed on a portable clinical trial information booth. This spatial device can spark conversations in waiting rooms and other event spaces.

close

close

Our Trial

Read moreNoah Cousineau, Vanessa Huang, Haoran Xu

Connecting former cancer clinical trial patients to newly recently diagnosed cancer patients, this community social program offers education and support. The system can introduce patients of similar ethnic groups to one another to share emotions and experiences.

After a user enrolls in “Our Trial”, they select which communities (similar cancers, etc.) they want to join. Users can choose to connect via chat or in-person. An online translation feature enables users to communicate with other different language users.

Warm “pop art” tones and fluid “groovy” shapes of the 60s/70s are used for the program’s brand identity. Posters, with the heading “Remember, You Are Not Alone,” depict photos of smiling people branded for ethnic communities. Similarly designed, brochure text includes common program questions and answers. Playful iconography can be understood by all cultures.

The logo can be interpreted as someone giving or receiving a hug. Hospital rooms can be designed for in-person Our Trial meetings and can include a couch and throw pillows fashioned in the curved logo shape. Other merchandise (t-shirts, etc.) can also be created.