This March, Art Center Product Design students Herbert Hsu and Kevin Heidkamp attended the 2013 Compostmodern Conference in San Francisco, supported by the Office of the Provost and Designmatters. They were accompanied by Product Design faculty member Dice Yamaguchi and Designmatters Fellow-in-Residence Muireann McMahon. The following is a two-part blog post in which both Herbert and Kevin share their unique Compostmodern experiences.

Temporary Items

This past weekend, a classmate and I were given the honor to attend the Compostmodern Conference in San Francisco on Art Center’s behalf. The two day conference’s main topic was sustainability, with a theme of exploring the term “resilience.”

![image[1]](https://designmattersatartcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/image1.jpg) Eighteen speakers, each with their own definition of the word, gave vastly different perspectives on how sustainability can and should be approached, and how all of it comes back to the power of design. Although eighteen lectures sounds like a lot, each was thankfully capped at only 17 minutes. I say “thankfully” not because the speeches were boring; on the contrary, each and every one of them was surprisingly engaging. But, as designers, I think we all tend to have rather short attention spans. And knowing their audience, the speakers knew that designers often work best with just a tiny crumb of a prompt, so that they can use their intuition to create very big ideas from something very small. Julie Sammons, for example, brought new meaning to “the 1%” when she told us the staggering statistic that 99% of Earth’s species have gone extinct. Anything living on this planet today has lasted the test of time, showing great resilience – and may offer compelling inspiration to design.

Eighteen speakers, each with their own definition of the word, gave vastly different perspectives on how sustainability can and should be approached, and how all of it comes back to the power of design. Although eighteen lectures sounds like a lot, each was thankfully capped at only 17 minutes. I say “thankfully” not because the speeches were boring; on the contrary, each and every one of them was surprisingly engaging. But, as designers, I think we all tend to have rather short attention spans. And knowing their audience, the speakers knew that designers often work best with just a tiny crumb of a prompt, so that they can use their intuition to create very big ideas from something very small. Julie Sammons, for example, brought new meaning to “the 1%” when she told us the staggering statistic that 99% of Earth’s species have gone extinct. Anything living on this planet today has lasted the test of time, showing great resilience – and may offer compelling inspiration to design.

Howard Brown, on the other hand, merely saw design as the reorganization of the Earth’s crust; this is a profound way to consider material consumption, and offers a new perspective on product design. He went on to examine consumerism in general by explaining that people buy products for their perceived benefits, not for the products themselves. In his eyes, products are merely vehicles for those benefits – benefits that don’t necessarily weigh anything or use any materials. Therefore, the vehicle may have the ability to change entirely, which is an intriguing sentiment for a product designer. He explained that when people buy a washing machine, what they really are looking to buy is clean clothes; when they are buying toothpaste, they are really after dental hygiene. The washing machine and toothpaste become arbitrary, which is creates opportunities for exciting new (and more sustainable) product designs.

Day two was much more interactive, as we moved from the Palace of Fine Arts to Autodesk’s office overlooking the newly-lit Bay Bridge for a workshop. The expansive space felt more like a gallery than an office, with interactive prototypes and models throughout. We were split into eighteen teams of about ten, each team with the same mission: to create a forty-eight second video that best defines “resilience.” The teams were chosen so that everyone was grouped with people they didn’t know – forcing us to go out of our comfort zones and be resilient ourselves. This was daunting at first, but I found the nerve to speak up, and to collaborate with other designers. Our video resulted in us creating a spectacle in and around the Ferry Building, using resilience to adapt and shift our approach in engaging with bystanders. We ultimately formed a conga line that included a street performer, and another activist group also looking to connect. By combining efforts, all three groups formed a collective interest in each others’ causes, and gave us all much more influence of the onlooking crowds than any of us had as separate entities. It also earned my team a top 3 finish during the final judgement of all of the teams’ videos. We were awarded with a recycled trophy that amusingly had someone else’s name on it. The name was of an unrelated person given at an unrelated event for an unrelated honor. And yet, by the end of the weekend, I realized that this notion of being unrelated simply doesn’t exist; everything is connected, related, and shared. The trophy itself being a beacon of resilience, it was the perfect prize to cap off a great weekend.

Day two was much more interactive, as we moved from the Palace of Fine Arts to Autodesk’s office overlooking the newly-lit Bay Bridge for a workshop. The expansive space felt more like a gallery than an office, with interactive prototypes and models throughout. We were split into eighteen teams of about ten, each team with the same mission: to create a forty-eight second video that best defines “resilience.” The teams were chosen so that everyone was grouped with people they didn’t know – forcing us to go out of our comfort zones and be resilient ourselves. This was daunting at first, but I found the nerve to speak up, and to collaborate with other designers. Our video resulted in us creating a spectacle in and around the Ferry Building, using resilience to adapt and shift our approach in engaging with bystanders. We ultimately formed a conga line that included a street performer, and another activist group also looking to connect. By combining efforts, all three groups formed a collective interest in each others’ causes, and gave us all much more influence of the onlooking crowds than any of us had as separate entities. It also earned my team a top 3 finish during the final judgement of all of the teams’ videos. We were awarded with a recycled trophy that amusingly had someone else’s name on it. The name was of an unrelated person given at an unrelated event for an unrelated honor. And yet, by the end of the weekend, I realized that this notion of being unrelated simply doesn’t exist; everything is connected, related, and shared. The trophy itself being a beacon of resilience, it was the perfect prize to cap off a great weekend.

Ready to Give a Punch

Drop a rubber ball, it bounces back. Take a closer look, the molecules of the rubber absorbs the force, and deforms when it hits the ground. Then it releases the force and returned to its shape again. It’s all about resilience, the topic of Compostmodern 2013, a metaphor for design to improve society and the environment.

The world, the ecosystem, and human society are like living organisms which have the quality of resilience. Why? They are consisted of countless participants with interrelated bonds that connected them as molecules. This quality allows them to take a punch, adjust, and then fight back. But how does it relate to design? If we say the duty of designers is to create a better tomorrow for the world through design, then the challenge for designers in this era is to finish the same task with resources getting rarer on Earth and the society having more unrest. At the Compostmodern conference, I saw the different approaches that designers, thinkers, and activists take regarding this issue.

Regarding the scarcity of resources, Howard Brown talked about the idea of resource performance in designing. He argues that designers should prepare for an invisible design revolution because people purchase benefit that comes with the product, which is weightless, rather than the product itself. Therefor there is the huge opportunity for designers to rethink what product design means by providing the same benefit with a lot less material. In terms of framing design problems, Terry Irwin suggests that designers learn to understand the wicked problem of a complex system behind a simple design task. The task is more than what is shown superficially. As Joan Thackara challenges the paradigm of designing and selling better, more efficient products, we should ask why purchasing is the only way for us to have the product we need. One instance can be found on Adam Werbach, who created the website Yerdle to show how sharing items can become new shopping and create nonlinear economy of products.

Regarding the scarcity of resources, Howard Brown talked about the idea of resource performance in designing. He argues that designers should prepare for an invisible design revolution because people purchase benefit that comes with the product, which is weightless, rather than the product itself. Therefor there is the huge opportunity for designers to rethink what product design means by providing the same benefit with a lot less material. In terms of framing design problems, Terry Irwin suggests that designers learn to understand the wicked problem of a complex system behind a simple design task. The task is more than what is shown superficially. As Joan Thackara challenges the paradigm of designing and selling better, more efficient products, we should ask why purchasing is the only way for us to have the product we need. One instance can be found on Adam Werbach, who created the website Yerdle to show how sharing items can become new shopping and create nonlinear economy of products.

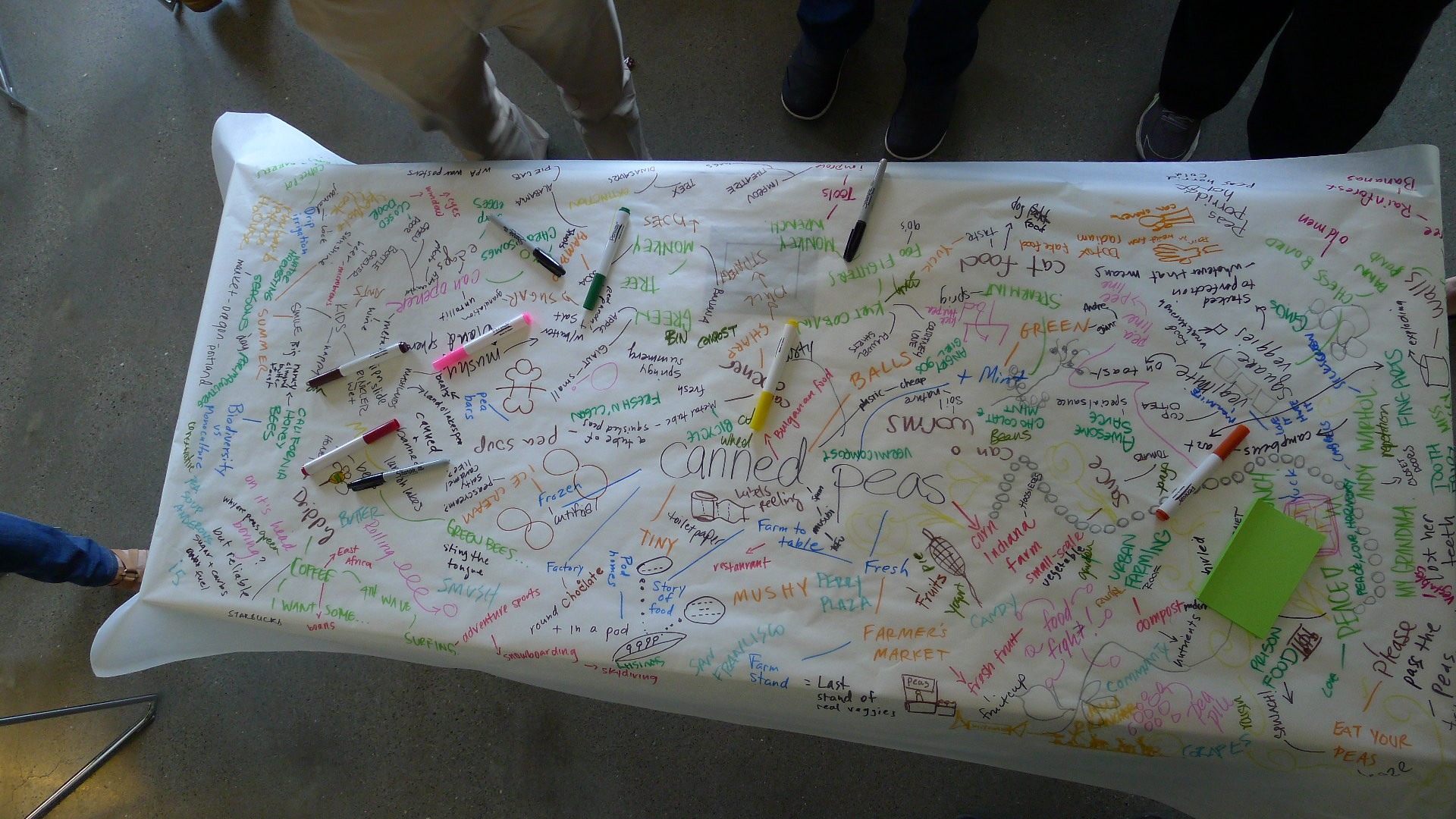

It is interesting to see that there are many designers in the conference suggesting similar approaches (which they have already put into action) of doing design. Those approaches can be summarized as: starting from local neighborhood, rapid making and prototyping in a real scale, and using participatory and cross disciplinary processes. Alex Gilliam demonstrates his project involving young kids in the community making street furniture in the public space. Designers should move their design meetings to the sidewalk, he said we can really find the real need of the city.

Jeff Barnum from Reos Partners holds the same idea that design solutions work only in its location through relationships in the community when it comes to complex social systems. That’s the why he thinks designers can only make interventions, not only specific design solutions. Joan Bielenberg uses his Project M to manifest the creative process of real intervention in society, which encourages designers to start the designing from the spot they’re not familiar with. Jump out of your comfort zone and think wrong, make small bets and let our mind to learn from them. He uses the same approach in the second day of the workshop to let the audience really practice how they can come up with ideas to show and manifest how resilience can help people take a punch.

The best takeaway from the two-day conference is that there is a paradigm shift happening in design: we should be aware that the design problem is always more complex than how we usually frame it. It does not mean we should spend more time to do research on it, but instead we should make work and interfere with it. We should learn not to think only about designing for the people but try to design with the people in the context. Designers must realize that the design process and their abilities are flexible and resilient and that we should be able to make ourselves think and design differently. We also must realize the world and society are resilient which allows us to try some small wrongs to find a better way of designing. It also means being prepared to work with the resilience of the world when it bounces back in terms of climate change or social unrest. A designer’s job now is to be respectful and trusted answering the question connecting social and natural issues. Designers must be ready to receive a challenge and give a punch. Are you ready?

The best takeaway from the two-day conference is that there is a paradigm shift happening in design: we should be aware that the design problem is always more complex than how we usually frame it. It does not mean we should spend more time to do research on it, but instead we should make work and interfere with it. We should learn not to think only about designing for the people but try to design with the people in the context. Designers must realize that the design process and their abilities are flexible and resilient and that we should be able to make ourselves think and design differently. We also must realize the world and society are resilient which allows us to try some small wrongs to find a better way of designing. It also means being prepared to work with the resilience of the world when it bounces back in terms of climate change or social unrest. A designer’s job now is to be respectful and trusted answering the question connecting social and natural issues. Designers must be ready to receive a challenge and give a punch. Are you ready?

For more information about the Compostmodern Conference, visit: http://compostmodern.org