In the following blog post, Designmatters Vice President, Mariana Amatullo shares experiences from her recent trip to Johannesburg, South Africa for the 2014 Cumulus Conference.

“ I was overwhelmed with a sense of history.”

– Nelson Mandela, The Long Walk to Freedom, 1994.

In an often-quoted passage to the conclusion of his autobiography, Mandela speaks of this sentiment as he reflects back to the momentous day of his presidential inauguration in 1994. Behind him were the beginnings of the successful restructuring of the South African system that repealed apartheid. Ahead of him, the complex transition to a nonracial democracy had commenced.

In an often-quoted passage to the conclusion of his autobiography, Mandela speaks of this sentiment as he reflects back to the momentous day of his presidential inauguration in 1994. Behind him were the beginnings of the successful restructuring of the South African system that repealed apartheid. Ahead of him, the complex transition to a nonracial democracy had commenced.

Mandela’s statement encapsulates how it felt to visit South Africa. Last September, I traveled to Cape Town and Johannesburg for the first time, on the occasion of our Cumulus Association board meeting, which coincided with World Design Capital 2014, and the first Cumulus conference in the region, “Design with the Other 90%: Changing the World by Design,” (a title inspired by the Cooper-Hewitt National Museum eponymous exhibition series). Long in the making, the conference was co-hosted by the Greenside Design Center and the Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture (FADA) of the University of Johannesburg. With the participation of a distinguished group of practitioners, academics and doctoral students from the region, the international event focused on notions of respect, responsibility and sustainability, and sought to catalyze discussions about the role of art and design in “sustainable social advancement, particularly in the context of the African continent.” From my local colleagues’ presentations I was left to ponder a number of debatable strands that seem gradually more relevant to the realm of social design, and to the diversity of reflective educational models many of us in this space of practice and scholarship strive for. For example, some of the papers and case studies that were shared touched upon post-colonial representations of visual culture; others reflected on the challenges of designing in resource-constrained and volatile socio-political environments across a multitude of stakeholders; many surfaced the frequent naiveté and unintended consequences of well-meaning design for development interventions; and others still addressed the limits of users’ participation and agency within many of the co-design methods routinely championed by designers. In addition to the weighty criticality of many of these topics, and perhaps because of a meaningful sense of place I somehow could not shake off, these conversations took on a fresh sense of vibrancy and urgency for me. “WHERE IT’S AT”—the bold title of a recent Design Indaba publication which I was gifted by that team only a few days earlier in their offices in Cape Town—kept resonating as a proclamation infused with confidence and contradiction….

After two decades of democracy, the South Africa I encountered has become a very different place politically, racially and socio-economically than when Mandela was inaugurated. By all accounts, the promise of the “rainbow nation” stands strong, and despite ongoing undercurrents of systemic violence and crime, unsettling allegations of corruption in its political leadership, and profound economic disparities, the two urban centers of South Africa that I visited show many physical signs of the “Africa rising” renaissance that we read about increasingly in the western press. In sprawling cities like Johannesburg, some of these changes are, in no small part, driven by policy and urban re-design initiatives that are meant to not only create economic renewal, but also pro-actively reverse the still visible remnants of the “spatial apartheid”—a meticulously designed geography of racism that reminds us of the disturbing complicity of wrongful design in enacting human right violations. Today, one of the most ambitious civic projects in Johannesburg, the “Corridors of Freedom” plan, envisions “re-stitching our city to create a new future,” and with this very aspiration positions design back as a fundamental affirmation of human dignity. Notably, the plan calls for the design of people-centered arteries for mobility and transport with, for example, new cycling and bus lanes and pedestrian walkways strategically laid onto a web of social infrastructure and mixed land use that is meant to usher in a new era of access and opportunity. It is an exciting vision, and one that seems to be already manifesting in discreet projects underway in central downtown areas of the city.

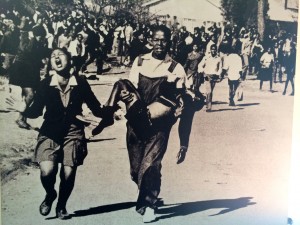

Sam Nzima’s photograph of Hector Pieterson being carried after being shot by South African police, Soweto June 16, 1976. Installation, Hector Pieterson Museum, Soweto.

Back to my being overcome with a sense of history during my all too brief and sheltered wanderings outside the conference venues. That surge of emotion came on at once, and unexpectedly, during a casual conversation with the driver of a local taxi, after the conference ended, as we drove with a colleague to the outskirts of the city and the site of the Apartheid Museum. The familiar question and exchange that often initiates many of the ephemeral conversations of travel journeys—“Where do you come from?”—prompted the driver, a father of four in his 50s, to tell us about moving away to safety in the mid-1970s from one of the townships of Soweto where he had grown up, in order to attend an English speaking school in the countryside. Suddenly, Sam Nzima’s iconic photograph of the dying 13-year-old schoolboy Henry Pieterson was no longer simply a famous museum artifact that has come to symbolize the tragic events of the Soweto uprising around the world. It was much more than a photograph, which I had just contemplated in stunned silence a couple of days earlier during my visit in Soweto. Now, it was an image brought alive by, and transformed into the hopeful outcome of this individual to whom I was talking, who had lived that moment in history as a middle school student, and had emerged alive.

The American philosopher Richard McKeon reminds us that “human freedom is one instance to move: it is self-determination as opposed to restraint or coercion.”* This is a truth that resonates with new meaning for me after this visit to South Africa.

* Richard McKeon, Philosophic Semantics and Philosophic Inquiry, from Freedom and History and Other Essays, edited by Zahava K. McKeon, 1990