This conversation is about the value of data design in local government and arts administration and the dynamics of collaboration between two designers: W. F. Umi Hsu, Digital Strategist at the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs and ArtCenter Media Design Practices (MDP) adjunct faculty, and MDP alumna Judy Toretti.

In this joint interview, Hsu and Toretti discuss the process of developing the Neighborhood Arts Profile and the implications of leading a government data project with design.

TORETTI: After graduation from MDP at ArtCenter, I started defining myself as a designer, researcher, and strategist. Speaking to other designers that probably seems redundant because we all are designers, researchers, and strategist. I do this intentionally, however, for potential clients and people outside of the design world. This helps get me to the table sooner. For instance, a graphic designer would typically get the design brief well after it was created – after all the initial conversations have already happened. Expanding my title to also include researcher and strategist, has helped make me a part of those early conversations, so that I can help define and shape the project from the beginning.

HSU: I fell into design by accident. I have a PhD in ethnomusicology and identify as a humanist-doer type: somebody who has a humanities background, who likes to think about big questions while being in the matrix of routine everyday work and personal life. After graduate school and a postdoc fellowship, I realized that I was interested in delivering on the social consequences of humanities knowledge. It’s been fortuitous to have been introduced to the ArtCenter Media Design Practices circle and its network of creative thinkers and doers. Not only are they engaged in their own practices as designers, but they also are able to speak broadly about what design can do in a larger human society. It was like meeting kindred spirits.

I love that MDP folks push the boundaries in what design could do in the 21st century world that we live in. Our lives are more complex now, with lots of moving parts. Institutions are changing. Our political systems are evolving. There is a chipping away of the nation state. From these behemoth system shifts, we notice that these systems that we have inherited don’t account for recent changes brought by technology, human migration, or capitalism. How do we continue to thrive as humans within drastically shifting contexts? It’s becoming an imperative to be nimble, efficient, and to leverage data in order to be more informed in multiple areas of life.

Recently I had an epiphany while listening to Bryan Boyer talk about strategic design on Scratching the Surface podcast hosted by Jarrett Fuller. The notion of strategy for systemic change resonated with me as someone with a humanities background with a curiosity about large scale problems and a desire to bring opportunities and necessities for change to surface. The systems that I work with are infrastructures of information, data, digital objects, communications, workforce, as well as systems of people or stewards – i.e. people working within an institution with convergent and divergent values and ideologies. Making sense of these systems and working with them to create change are core to how I think and operate in the world. Design can help us navigate system shifts. It can deliver collective ideation moments that lead to the genesis of something tangible like an institutional process or a tool to reorganize thinking and behaviors.

TORETTI: Right, and thinking about these potential new tools and data driven work along with the shifting world dynamics, we now have access to all this data at our fingertips. What do we do with it, and do we want to do anything with it?

HSU: At the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, our general manager Danielle Brazell has led the agency with the question of how do we perform as a 21st century progressive arts agency. It was then It my job to answer that question from my particular perspective of design and figure out how to implement that vision. We’ve been doing a lot of work including a cultural asset mapping initiative, a lab to cultivate staff digital literacy, Arts Datathon to collaborate with the public through data, and more broadly, developing a design strategy to build the scaffolding for this 21st century agency.

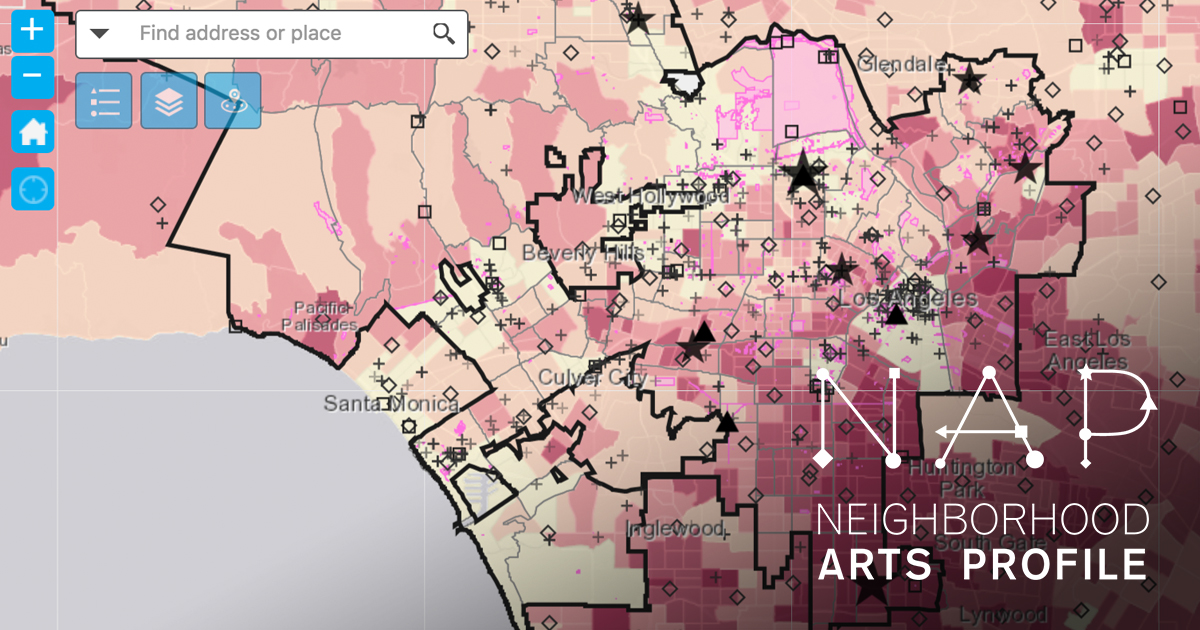

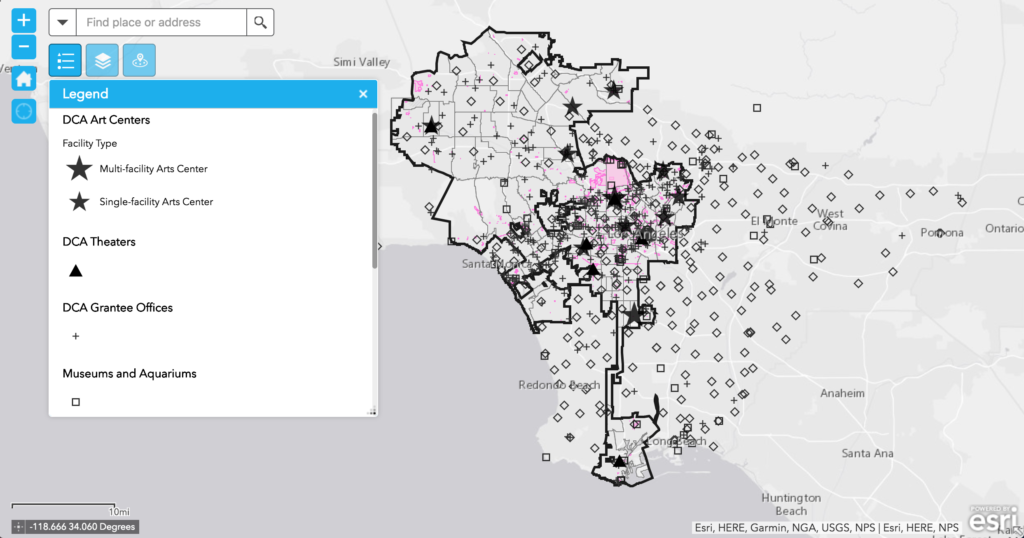

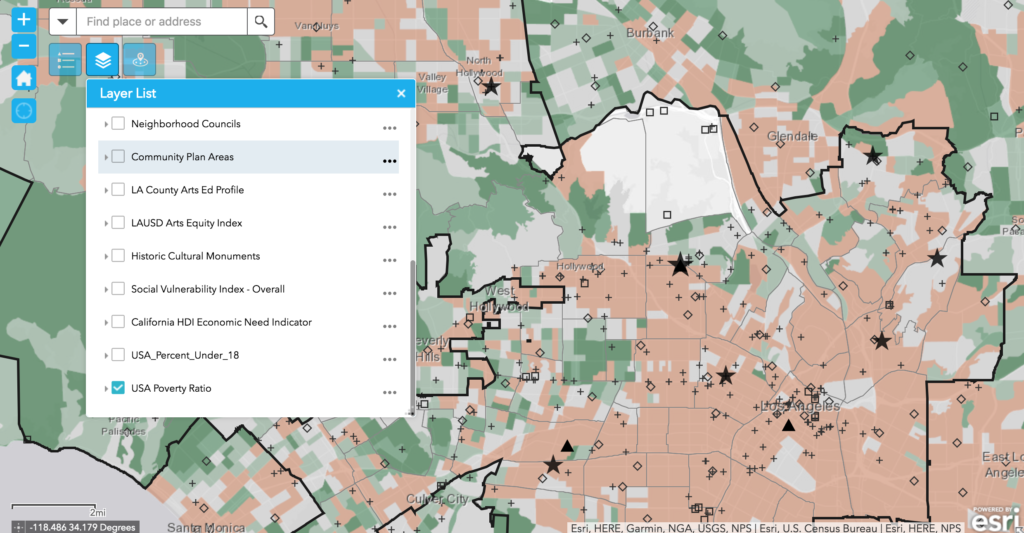

All data are not born equal. Off-the-shelf analytics products don’t generally include arts and cultural data. We had to create a tool that forwards our mission. Neighborhood Arts Profile (NAP) is our version of a business intelligence tool. Because we are in the business of creating meaningful and accessible arts and cultural experiences in the City, the design of NAP is led by these values. We wanted to build a tool that can help us visualize cultural vibrancy and community wellbeing (e.g. poverty rates and access to in-school arts education) in each neighborhood in Los Angeles. Organizationally, we wanted this project to put us all on the same page informationally and help us connect across our work silos. To see that while we may provide different services, we are serving the same communities was a key objective. Using a human-centered approach to reflect on our programming, we asked questions like: How might different neighborhoods experience arts and culture? How are those communities doing socioeconomically? What might the value of our services in light of other arts and cultural infrastructure in the city?

TORETTI: When I went to the Arts Datathon, I was overwhelmed by the amount of data that was available. I kept wondering what the end result would be. What’s the drive to collect this data, and what’s its purpose? Then, when we met to talk about the Neighborhood Arts Profile, even though we knew it was going to be a tool for business analytics and we knew the Mayor had this open data initiative, the tool still needed to come together in a tangible way. I remember during our initial conversations, I kept thinking, “what does this look like? How can we make this all come together?”

This was one of my first times working with this amount of data. When I was worked with the Los Angeles Fire Department, we considered three or four datasets: roll out time, time to incident, number of incident, etc. It was clear what the Fire Department needed, but in this instance, there were two driving forces: one, the data that was collected; two, the questions: what does this tool look like and need to do for this department?

HSU: Part of what’s exciting about the NAP project is that it challenged us to ask harder questions. We are used to talking about things in a certain way, but the people we want using this tool don’t talk about data and design the same way we do. This is a classic human-centered design situation. I can design a tool that I will use, but no one else might use it.

It’s been great to have you ask us hard questions. Your questions made me have to chew on the following; who’s actually going to be using this tool? What are their various relationship to data and this tool? Who is our primary user group; who is our secondary? The technological aspect can be figured out, but these harder questions about user and contexts needed to be addressed first. I was excited about the idea of leading this project with design in order to figure out the specifications and usability of a tool that will eventually increase the staff capacity and help the department work in more dynamic and impactful way.

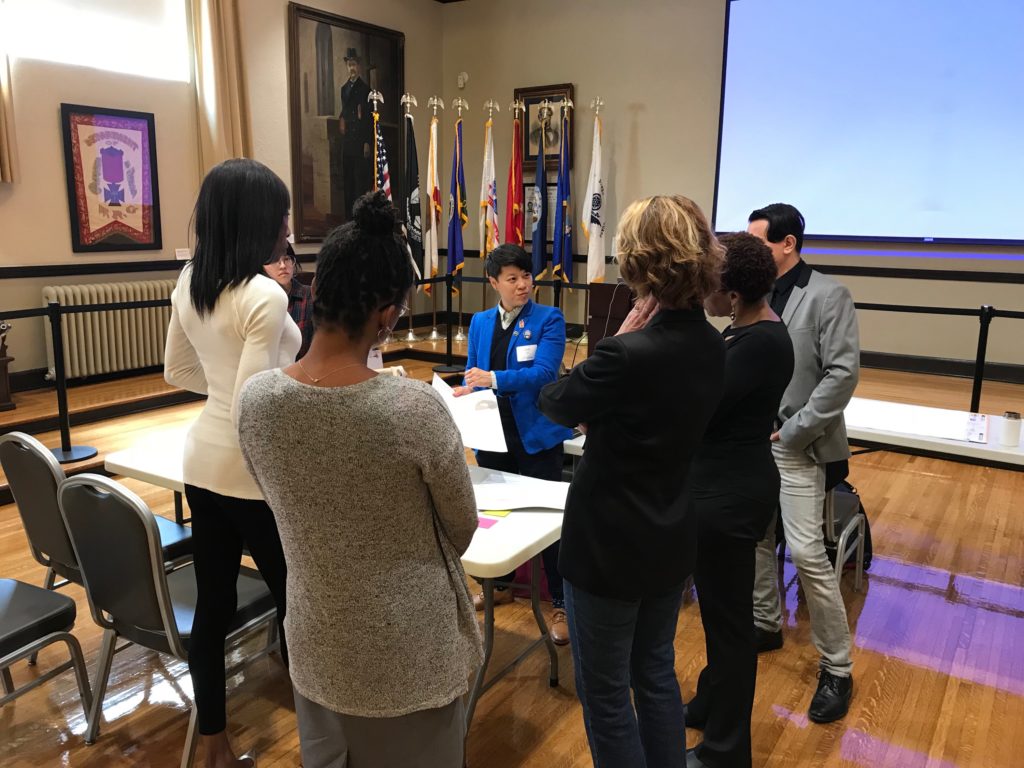

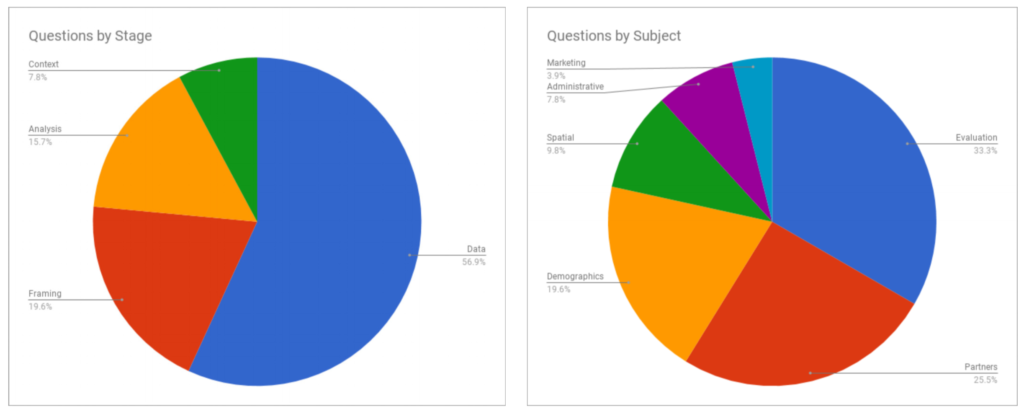

TORETTI: Our design workshop with the department staff is a great example of leading with design. The workshop centered on what questions they would ask that the tool should answer. I remember when we began, there were confused expressions in the room. So I said, “Umi, Izzy, and I can sit in a room together and based on what we believe to be the needs of this tool, create something that would hit every request that department’s management has put forth for this project. I don’t think that’s the way to go. I don’t think this tool will have longevity, and we’re really building this for all of you. What do you need?” That started a larger conversation about what questions this tool could address.

HSU: Asking a question is a moment of human agency. When someone asks a question, it not only comes from a place of curiosity but also from a place of experience and analysis. City staff are often on the receiving end of having to answer questions, responding to information requests from the Mayor’s Office: How much fund is being expended for a particular program? What’s the impact? We are always looking for answers.

To be proactive in this age of information anxiety, we want to support a cycle of meaningful inquiry and analysis in a large bureaucracy. We want to create a culture in which it’s ok to ask questions and have access to a tool that can help us find answers. I think our design workshop kicked off this sort of thinking. With a tool to help us gain access to reliable and actionable data, we can change the culture to one in which it is actually okay to ask questions, and we can scaffold our inquiries so that we don’t have to have an answer for everything at all times.

Another moment worth sharing is about our work symbiosis in terms of research design ad design research. Traditionally, the social science approach is the go-to method in policy research and evaluative research about the impact of a government program. In that instance, an external researcher comes into a program to validate it with an attempt to identify connections between the program intent and output and outcome data. Our approach to this project is syncretic. It brings together components of social science research and the collective inquiry-driven approach of design research. Instead of having an external scientist conducting a test to look for evidence of impact, we wanted to empower staff users to be able to design a tool so they can use to better do the work they do. This approach is not meant to answer the big summative evaluative questions regarding impact, but it can help us answer effectively the smaller questions about potential programmatic opportunities based on the analytics of service need.

TORETTI: Yes, by coming at the project while foregrounding design research, participatory design, and human-centered design, we gave the decision-making power to the staff. Traditional science is more researcher-driven and feels stagnant. By doing design research, we continually shared our work with the staff to make sure we were on the right track not just with the design brief but also for their needs as they were beginning to understand them. There was a collective sigh of relief after finding out that we were not external forces coming in to make these determinations for the department.

HSU: We’re working from the context. The context here is the department’s culture and staff, who already have a wealth of knowledge. We treated our staff as subject experts, and people who would eventually be users benefiting from the project. That was a refreshing surprise. And because we’re design research nerds ourselves, we have documented this participatory process and shared it with design templates and artifacts on Github.

TORETTI: Having you as an internal staff member really helped with that process because it wasn’t an us versus them mindset. You warmed them up to this idea of data, the use of data, and the potential of data. Because of your role within the department, we had a bit of a running start with this project.

HSU: Yes, I often end up being a translator. I become that classic ethnographer who is an insider in a culture but also having to play an outsider to translate from the inside out and from the outside in. In this instance, I helped translate data ideas from the tech and private sector into language we use here. Then building a prototype to illustrate how these ideas would play out within specific work contexts helped our staff make sense their data world and imagine the utility of such a tool. Maybe having a bicultural upbringing helps me prepare for this sort of work.

TORETTI: A surprise to me was how significant and meaningful this prototype has come to be for the department. We have always talked about this as just a prototype for a larger tool that would be more dynamic with more analysis, but this first step was a big moment. It was more significant than I thought it would be, and that was really exciting to me.

HSU: I’m happy to hear that. I am continuously learning how design helps us understand each other and figure out how we can work toward a common goal. Not only as two designers we are working together and challenging each other’s assumptions, we are also discovering ways to use design to help an organization concretize a set of unrealized aspirations. Leading this change with design, we can lift inspirations above routinized work and work toward a more focused and shared agenda.

W.F. Umi Hsu (pronouns: they/them) is a strategic designer and public humanist who engages with research and organizing agendas for equity in arts, technology, and civic life.

Judy Toretti is a designer with a background in traditional design and a passion for design thinking, strategy, and research. She uses design to analyze systems, gather deeper user insights, and establish compelling visual narratives.