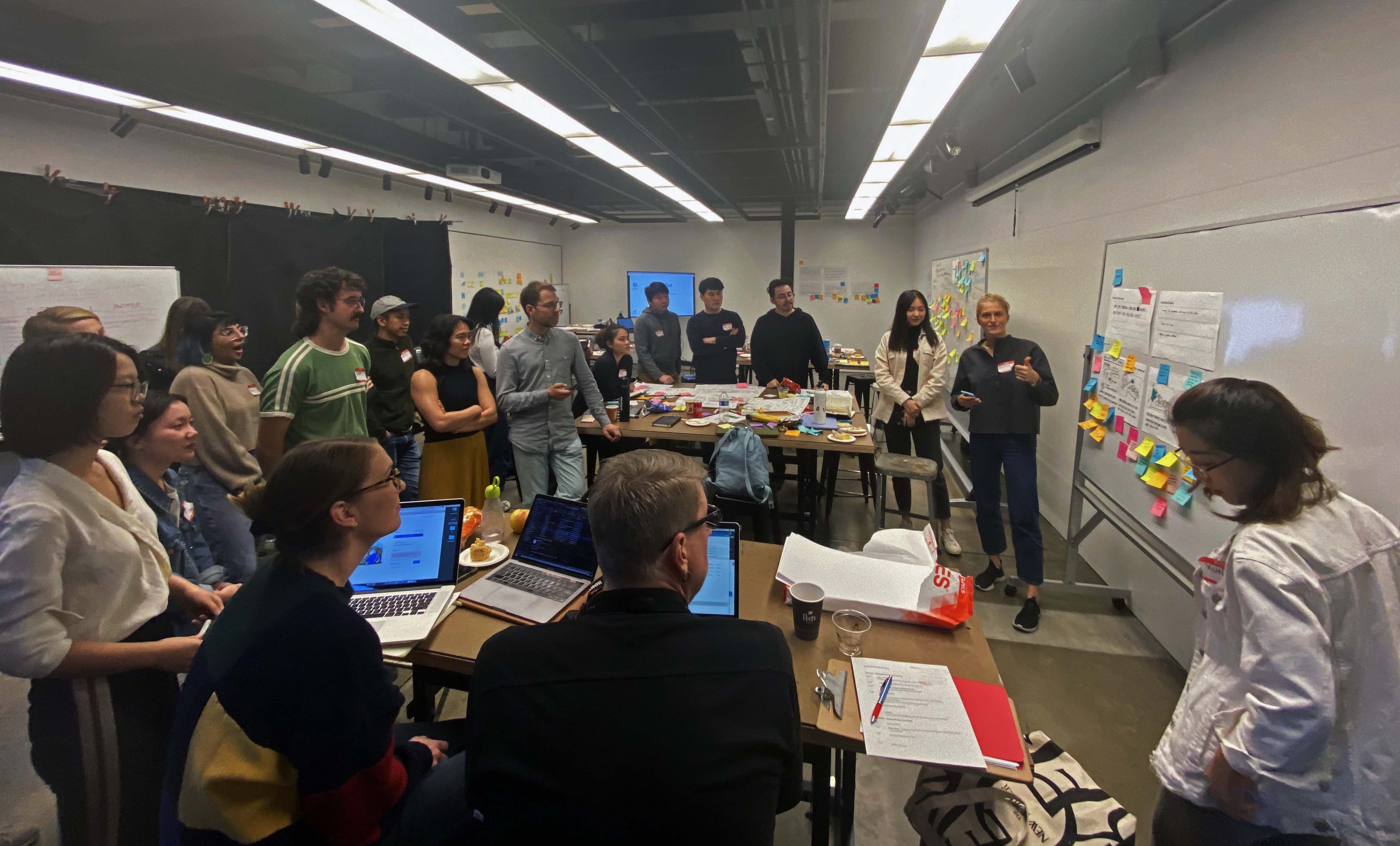

A few weeks ago, we welcomed Designmatters’ Resident Josh Halstead (BFA ’12 Graphic Design), a design leader and disability advocate, to spend the week on campus sharing his thoughts and expertise with the ArtCenter community. As part of his residency, Josh, along with two representatives from Google – visual designer, Aldis Ozolins ( BFA ’12 Graphic Design), and interaction designer, Dru Bramlett,— lead a workshop around accessibility and design. There was a lot of interest around the workshop, and with limited space, I was grateful to have the opportunity to shadow the day-long studio.

Many of the general assumptions about accessible design (most of which are untrue) keep designers from confronting accessibility issues. Consequently, these statements (i.e., accessible spaces are expensive to create, benefit a small percentage of the population, only require the bare minimum, can be tacked-on at the end, etc.) keep designers from forming successful solutions. Why are these myths still commonplace, especially in design? Some designers are not compliant or treat accessibility as something to be checked off at the end of the design process; this is a problem in the industry.

A designer can add Braille to their prototype and believe it’s accessible to anyone who is blind when, in reality, fewer than 10 percent of the 1.3 million people who are legally blind in the United States are Braille readers.

As Josh puts it, accessible design is universal design, and instead of coming at the end of the ideation process, it should be the basis of the design itself. “Disability is a mismatch between the needs of the individual and the design of the product.” (J. Halstead) If we expand our notion of who that individual is, then we can achieve a universal design. Whether a person is blind or seeing, if they can both tell the time on the same watch—and without compromise to the watch’s aesthetics—it is considered a successful design. To achieve a universal design like this, industries must hire disability experts to be part of the design team, not just at the end of the process, but as co-creators. We must have accessibility designers, and industry professionals lead future designers to create impactful experiences and set the standard for human-centric solutions as the norm.

Ultimately, the goal is to design with and not just for the individual user, and Josh, Aldis, and Dru set up the framework for that very lesson. The expertise is limited to the experience and knowledge of each individual, but if you pair that with the knowledge of someone that is an expert in accessibility, you may get a viable solution. The workshop started with a lecture, and in the afternoon, participants came up with a variety of solutions for several accessibility problems within the school, specific to an assigned persona. Abruptly, Aldis and Dru would announce that the personas were changing, and the teams had to reconfigure their design for this new accessibility need. I realized that it was less about coming up with the right solution and more about learning techniques to design more inclusively. Many of the ideas were extremely innovative, but they were just preliminary. What seems to be the biggest take away is that through these exercises, designers formed ideas that were closer to universal design, and subsequently more inclusive.

My understanding of disability and accessibility has evolved quite a bit in the last year, and to be honest, I wasn’t thinking about accessibility comprehensively. I never found myself in a scenario where I needed to stretch that notion—until last year. My mom was diagnosed with Central Cord Syndrome, likely from an acute form of degenerative arthritis in her cervical spine, putting her at risk of quadriplegia. After emergency surgery, and a year of rehabilitation, she has lost all feeling from the waist down. Although her situation has been difficult, my mom has maintained much of her independence. She’s fortunate in many ways, but it’s something that has been a mental and physical obstacle for her, and in turn, transformed the way I think about accessibility.

As a designer, I always try to look at things from a variety of perspectives, but I realize my scope is limited by my experiences—which is why workshops like the one lead by Josh, Aldis, and Dru are so meaningful. They offer opportunities for ArtCenter students to gain knowledge from industry leaders (who, in this case, are already designing for disabled populations) but industry leaders that move and inspire designers to come up with innovative and inclusive ideas.

Schuyler Walter currently works for Designmatters and the ArtCenter Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Dept. She is an avid painter, illustrator, graphic designer, and crafter. She is passionate about pursuing DEI and Social Justice initiatives and is proud to be on a team of hard-working creatives, educators, and innovators.