An astounding 54.6% of people 25 and older in Boyle Heights are without a high school diploma. Why is this? How can we help students who have dropped out of high school to stay motivated and continue school to earn their high school diploma?

My journey began in 2012 when I volunteered with Youthbuild Boyle Heights, a non-profit charter school for students who have dropped out of the public high school system. The time I spent there left a long lasting impression on me. My 16-year-old self could never have fathomed the struggles of students in Boyle Heights, from gang related deaths, to homelessness and drug addiction. These problems faced by the students are what drew me back to Boyle Heights.

Since then, the school has changed its name to Youthbuild CALÓ and has helped hundreds of students graduate. This summer marks CALÓ’s 5th and last year; with funding scarce and more and more public charter high schools popping up in the area, CALÓ can no longer afford to pay teachers and staff.

Using CALÓ as a case study and model, I worked with the students to see what their daily lives were like: what they liked to do, what they disliked, and what was the most stressful parts of their days. I wanted to understand what barriers stood between them and graduation.

I listened to what worked and didn’t work and tried to emphasize positive factors in order to keep the student’s driven. I learned that students wanted to feel supported by parents and faculty, that peer to peer pressure was a motivator and the path to graduation wasn’t always clear.

Students lost motivation due to lack of support from their family members, who were busy, often working two jobs trying to support the household. This environment led students to feel disengaged from education. They felt that even if they performed well, no one would care.

Another issue that emerged was the inability to visualize students’ progress, both for the individuals themselves and for their parents. With no sign of graduation in sight, this feeling of being in a void resulted in students losing motivation. People I spoke to expressed anxiety, feeling that their work was going toward nothing and progress was not visible.

In regards to planning for life after graduation and deciding on what career paths to take, I realized students had little information about career pathways besides what the adults in their life did for a living. This limited the type of careers the students took interest in.

Using these insights, I began to leverage factors that encouraged the students and incorporated these into my solution.

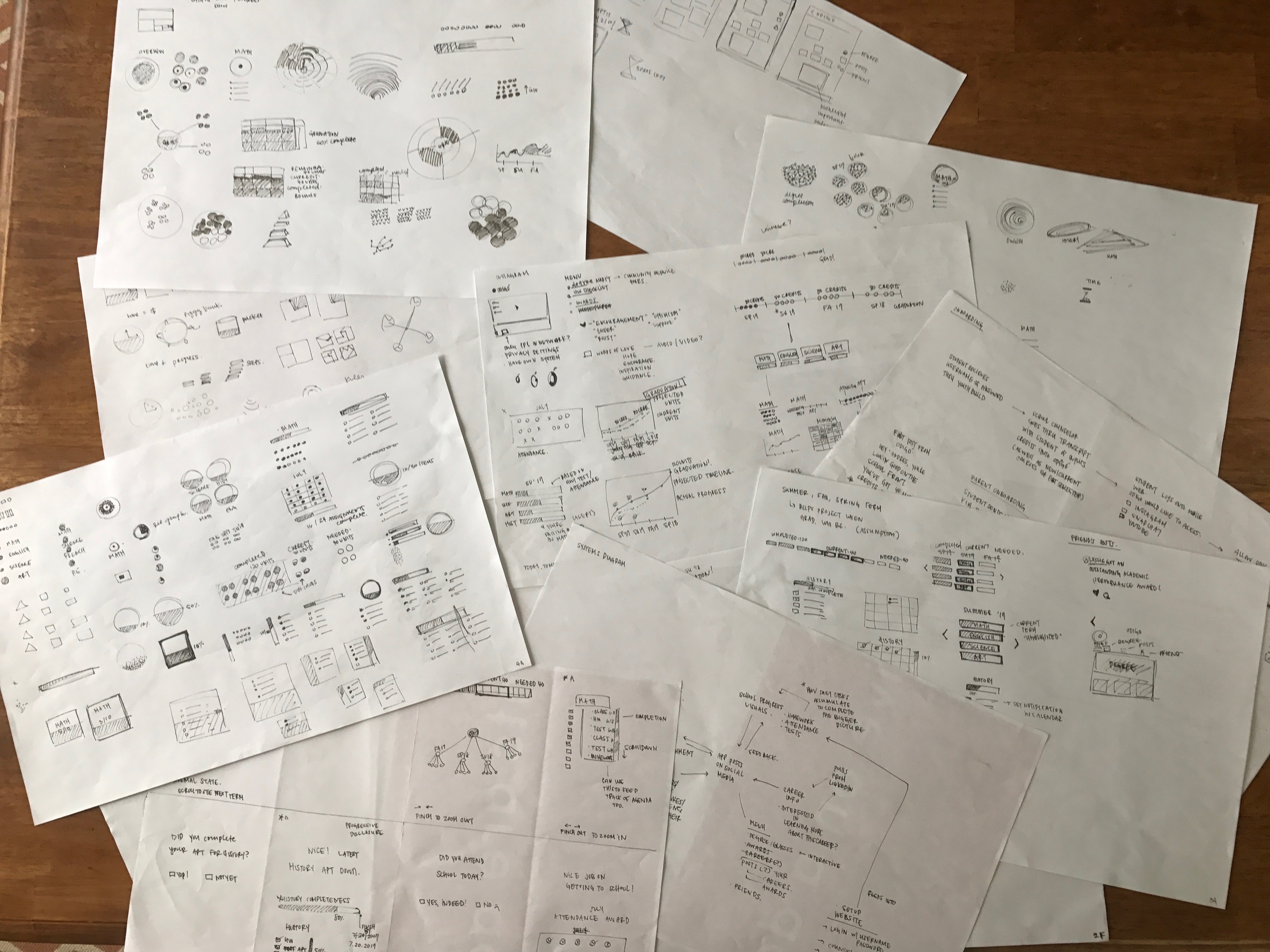

I utilized participatory design by having students validate my insights and ideate on potential solutions with me. This validation propelled me forward, trusting I was on the right path.

Meanwhile, persuasive technology grabbed my interest. Mobile phones are great platforms for persuasion and can help change people’s health behaviors. I used BJ Fogg’s model to determine that dropouts in Boyle Heights were actually high ability, but low motivation. This meant that I should simplify factors that prevent these students from reaching their goal, in this case, graduation. The easier it is for students to access my content, the more likely they would be to use the app and hopefully complete high school.

This was the reason designed my solution to live on a preexisting mobile app, more importantly, apps that students already use on a daily bases. I narrowed the list down to three social media apps that students used to digest media content: Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook. This way, content and updates would be pushed to students on platforms they are already on, thus eliminating the need to download yet another app.

My solution is Odigó, an app for students that lives on social media to visualize school progress, get encouragement, and discover future career pathways. The app provides progress visualization thru checkpoints and deadlines for classes and homework. Parents, peers, and staff can send boosts or words of encouragement when students hit milestones or complete tasks. This action is designed to boost morale and keep students motivated to continue to attend school by making them feel supported in their education. Finally Odigó pushes career information to students that may otherwise have no other way to discover these pathways.

My hope is that these students feel supported and encouraged in their daily lives and especially in their journey through education. Although Odigó targets just a slice of problems students face, it would be nice to know that my solution could have a ripple effect in their lives, eventually moving out toward the bigger picture after graduating high school.

If I could talk about one takeaway from this project, it’s that this process has made me believe in having the user help design solutions for themselves and their peers. Nothing is more reassuring than hearing your inklings validated and working together with people you’re designing for to create solutions you both believe in.

Mariko Sanchez is an Interaction Design student at ArtCenter College of Design. She draws from her education and experiences, with the goal of combining social impact and design to make people’s lives a little better.