Designing for Green Justice: Protecting the White Sage Campaign

- Social Justice

In this Designmatters studio, students explored the connections between Los Angeles’ indigenous past, present, and future relationships with native plant life – and the opportunities for non-natives to learn about the land they live on. The recent cultural appropriate of white sage “cleansing” by non-natives – and the subsequent destructive poaching of the sacred plant to fulfill demand – offered students a doorway into more complex issues involving stewardship of native habitats, indigenous land rights, and settler colonialism.

Students worked closely with members of the indigenous community including the newly designated Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy which is stewarding ancestral lands of the Tongva people in Southern California. Meeting with indigenous land rights advocates and tribal leaders along with research, readings, and field trips to sacred spaces provided students with a profound sense of the unity between earth, plants, and people.

Using social media graphics, infographics, and other visual elements, students created multi- media awareness campaigns that confront various aspects of contemporary indigenous cultural erasure while offering audiences new ways to respond and appreciate appropriate land practices that honor the cultural traditions of the first peoples.

“The global demand for white sage is harming this part of the world because we’ve made an object of it, instead of [seeing it as] a plant relative that is integral to a specific habitat. This comes from commercialization culture.”

Jessica Rath, instructor

Project Brief

Transdisciplinary ArtCenter students were challenged to investigate and create a campaign/project that would honor the indigenous peoples’ stewardship of native plant life while presenting information to a non-native audiences so they can act, respond, and appreciate the land practices that honor the cultural traditions of the first peoples.

In addition to delving into the historical context of settler colonialism and indigenous land rights, students learned about contemporary native habitat issues – including the poaching and destruction of white sage on sacred grounds culturally appropriate this plant as a “cleansing” ritual. This dramatic example presented the students with a flashpoint to ignite their design thinking.

Students had opportunities to meet, interact and co-create with members of the local indigenous communities. Field trips to sacred spaces offered students time to reflect on the unity between earth, plants, and people. Through multi-media awareness campaigns and branded educational tools, students addressed the unique aspects of contemporary indigenous cultural erasure while providing the audiences with tools and resources to honor the cultural traditions of the first peoples.

About White Sage and Poaching

An evergreen perennial shrub, Salvia apiana is an aromatic plant native to the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. Typically they are found in coastal sage scrub habitats in Southern California and Baja California along with the western edges of the Mojave and Sonoran deserts.

The plant is revered in many native cultures. Often it is considered a sacred living family member. Careful cultivation techniques have allowed this plant to grow tall and strong, sometimes living up to thousands of years. It is prudently harvested for ceremonial and other traditional uses including “smudging” or burning leaves in an open ceremonial dish.

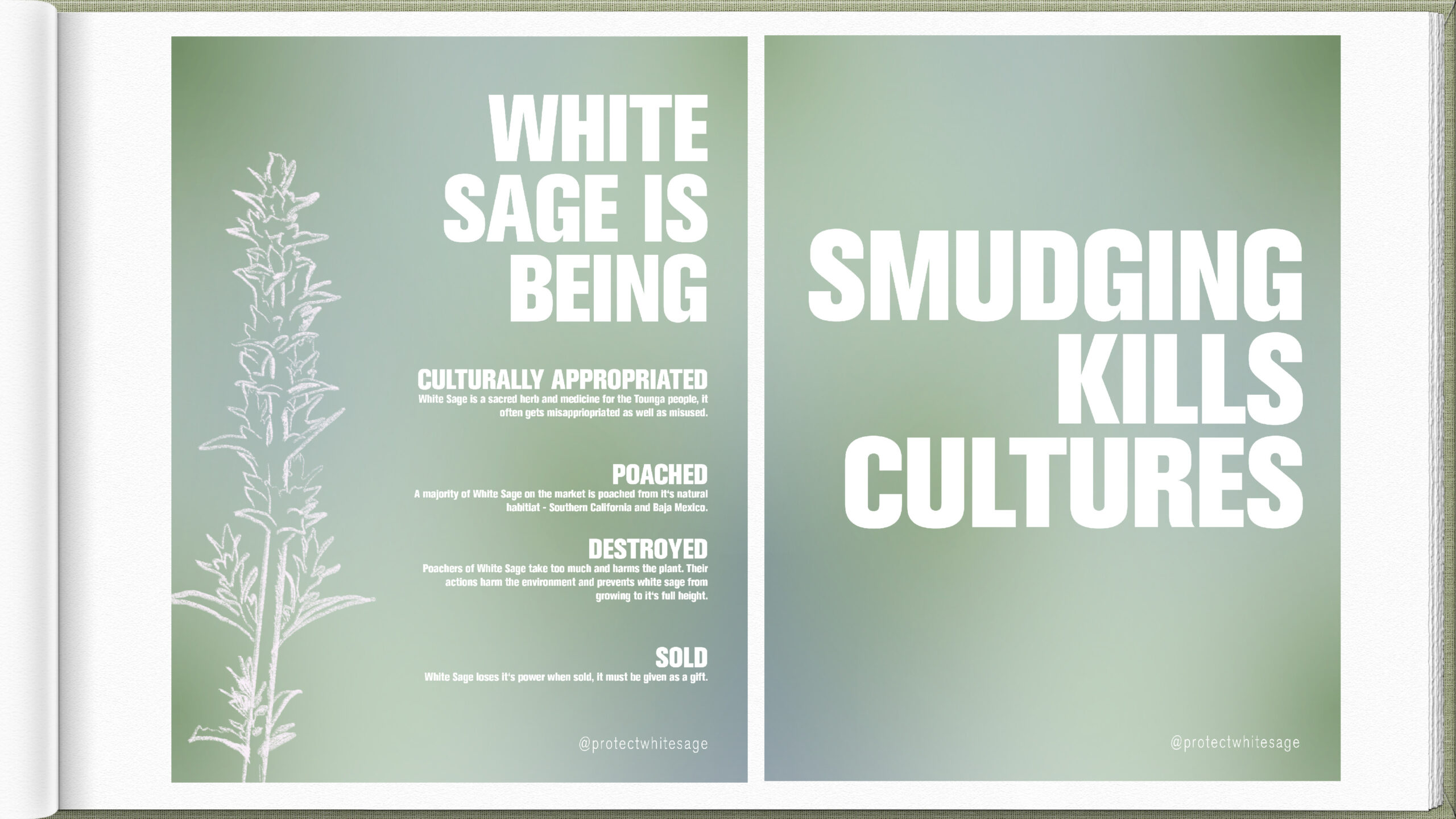

Over the past decade, however, smudging has been embraced by non-native groups causing a soaring international demand. Popularized in movies, television shows, and by trendy influencers on social media, burning white sage is a way to “cleanse the air.” However, these actions fuel an unscrupulous underground black market.

“Medicine [like white sage] shouldn’t be bought or sold. It’s considered a gift.”

Samantha Morales-Johnson (Tongva)

According to the California Native Plant Society (CNPS), poachers remove metric tons of white sage regularly, trespassing on private properties — often at night — to rip and hack off leaves, which often leave tall healthy plants in pieces.

CNPS estimates there are only a handful of commercial growers of white sage; the vast majority of white sage products on the market, sold in yoga houses, and online, have been poached.

In short, indigenous communities are experiencing not only theft of their sacred plant but also their ceremonial practices that have profound meaning that deeply connects them to the land and their ancestors.

Research and Project Development

To kick off the studio instructors explained their style of teaching by stating, “If we are not making mistakes, we aren’t doing something right,” and explaining how resources and reading materials would offer a deeper context to the history of native peoples and their relationship to land and plants.

Instructors discussed early California and how the first impressions of Southern California involved the land. With the rise of the mission system and the enslavement of the native people, man-made nature – gardens, orange groves, cattle, etc. – contributed to how the natural world was changed from its original growth.

Screening moments from the documentary “Saging the World” introduced students to issues involving the sacred plant which indigenous people see as family. The, “grandmother,” while others only see the plant as something to only acquire and sell.

Culturally appropriating the sacredness of sage – and attaching a monetary value to it – is one example of thinking that is steeped in colonialization and white supremacy, attitudes that still linger in the American landscape. Students were challenged to question: how do you best dismantle cultural appropriation? A lively discussion followed, and students realized that a good approach would be showing others that their own culture is as rich in the ceremony, etc. as the one they are embracing. After all, smudging comes from a long traditional belief in the spiritual power of burning a specific plant.

“It was important for us to start the studio with the visit to the Tongva Land Conservancy because we wanted to ground the work that the students would be doing into something tangible.”

Joel Garcia (Huichol), instructor

Continuing in the same vein, students were prompted to start thinking about ways their project could reach those who see plants as only a commodity (sellers) or a quick treatment (users). Since many individuals smudge as a method to “heal” from a bad relationship/job/experience, instructors questioned, “How do you tell someone they can’t heal?” and “How can we change

minds?” Throughout the course of the studio, students and instructors engaged in broad discussions and brainstorming. Assigned readings, podcasts, and in-class work and assignments offered students informational background on native plants but also challenged their own misconceptions and sparked their creative designs.

In addition to designing for a target audience with a specific message, instructors encouraged students to interject elements of reciprocity and to advocate for practicing to be honest stewards, educators, and protectors of the earth.

And finally, instructors reminded students that their projects must be co-created with members of the indigenous community. Overall, these campaigns will, “Not speak for them, but through your art, you will help uplift their voices.”

Understand, Observe, and Design

The first part of the studio immersed students in the culture, history, and issues facing the indigenous peoples. Field trips gave students in-person opportunities to deeply understand how the indigenous people interact and relate to the land, plants, animals, and each other.

The first field trip found the students on a shady hillside overlooking Eaton Canyon. In an outdoor stone circle, students gathered to hear from Samantha Moreales-Johnson (Tongva), an illustrator, steward, and ethnobotanist, who is also heading up the newly designated Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy in Altadena. Moreales-Johnson shared her personal connection to white sage noting how angry and sad it makes her to see the commercialization of sage, but also the larger tragedies of the current relationship of humans to the plants and land around them. She described the native view of medicine as not a commodity, but a gift you freely give.

As students considered their campaigns, Moreales-Johnson urged them to tell people that growing sage themselves can be a transformative experience. “We want people to grow it so the land can heal,” she explained. Moreales-Johnson showed how her tribe – and others – does not roll up sage into the sticks…how it’s often presented in videos and sold in stores. The tradition is to burn individual leaves in an abalone shell.

“Although these projects take a singular approach to the White Sage Campaign, they are interconnected and help advance one another.”

Joel Garcia (Huichol), instructor

Finally, Moreales-Johnson explained that for indigenous people, being removed from their land along with systematic racism is a heavy painful history to carry. Samantha had tears in her eyes describing what it means to have this land granted back to the native people. Before students left, they explored the grounds under canopies of native oaks, and contemplated what land means and how the plants, the trees, and the landscape can connect to and with humans.

Other trips included Eaton Canyon and the North Etiwanda Preserve in Rancho Cucamonga which has been targeted for years by poachers who have destroyed many white sage plants. Students were given a tour of the preserve by Nic Hummingbird (Apache and Cahuilla). Seeing the environment where white sage naturally grows helped students better understand the plant connection and the anguish of seeing it being improperly harvested (hacked) by poachers.

Teamwork and Processing

In the classroom student teams were formed, giving many a first-time experience working with an individual in a different major. Designing in teams gave students a hands-on experience in creative communication. As part of the research, teams examined the effectiveness of others’ “campaigns” that challenged cultural appropriation, noting what worked and what didn’t. Other environmentalists and community stakeholders made in-class presentations on different aspects of the issues which provided students with even more opportunities to fold into their research and ideation.

Teams had opportunities to interview and reach out to experts learn how to formulate compelling questions, and actively listen while being conscious of their own biases. Students learned the distinction between speaking for the native tribes – lest them appropriate knowledge, and working with them to bring attention to this important issue.

Students explored how their messaging could best be presented, examining spatial design solutions, installations, illustrations, and other creative outcomes. Overall, they were challenged to see how their design thinking could undo systems, norms, and assumptions, disrupting contemporary thinking and visualizing the impact of their actions. While teams actively worked on their projects, in-class discussions provided a wide scope of themes that nudged students’ thinking about bigger themes such as environmental equity and justice along with indigenous land practices. The topic of how climate change is impacting urban ecosystems led to ideas/concepts on how to best advocate for envisioning green spaces and restoring native habitats.

“Los Angeles and its fast-paced environment, [has] never taken time to appreciate the natural resources that California has to offer. It was wonderful to learn more about the land you live on – and what the native plants offer to us. We as people who live here can pay more attention to the ecological aspect of the land to nurture it.”

Nati Raya, student

During midterm presentations, community stakeholders and partners heard and saw how the students’ design thinking translated into a possible effective campaign. Feedback was very important at this point; it could swerve a design idea elsewhere or help solidify a current concept. Teams explained the research they conducted as well as what they learned so far – and how that all informed their ideation. Interestingly, each team chose a unique aspect of the larger issues covering such topics as advocacy, engagement, public consciousness, and the built environment.

Fueled with feedback from the midterm, teams continued to refine and shape their projects; many sustained communications with experts. Prototyping their concepts gave the student a deeper sense of bringing their ideas to life – whether it was through an illustration, digital component, or spatial forms. As they worked, students kept circling back to how this concept will answer the challenge, how their design thinking could provide context and uplift and shine a light on what indigenous people have been saying and doing for centuries.

Outcomes

close

close

White Sage Zine

Read moreNati Raya, Chet Taylor

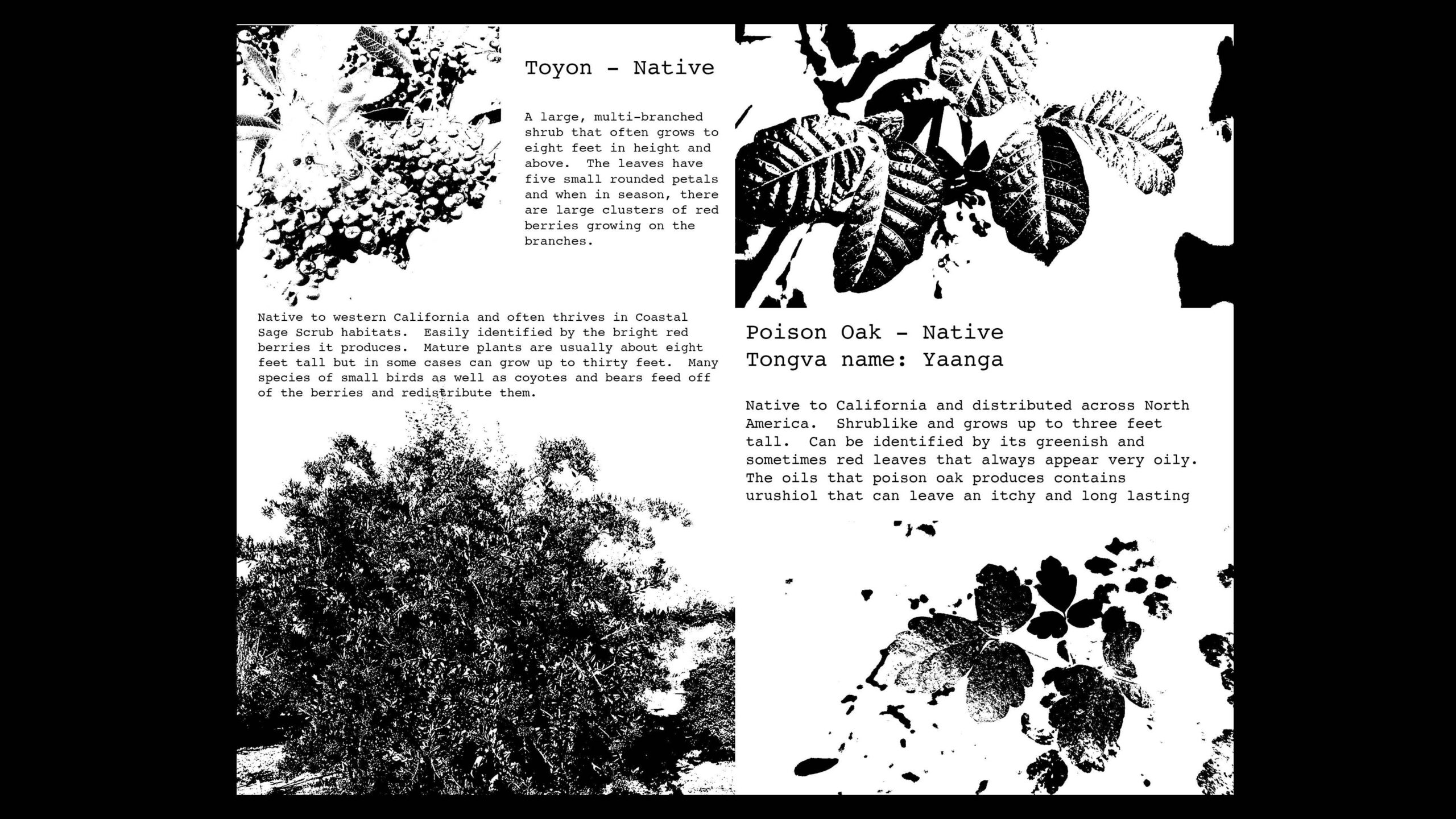

Presented in a gritty style, this black-and-white zine presents an overview of the natural history of Southern California ecology and the relationship of the early people to the land. The zine will be distributed in public spaces, nurseries, and stores.

Showing where the historic Tongva people lived, the zine reminds readers that the indigenous people are still here today. The zine provides illustrations, history, and cultural connection of native plants – white sage, toyon, oak – to the early peoples. It also presents non-native species found here and how these plants negatively affect their environment.

Finally, the zine encourages readers to visit native species in their habitat (Etiwanda Preserve, etc.) and includes QR codes for information about white sage, native species, and the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy.

close

close

Efflorescence

Read moreKatherine Shirinyan, Elinda Xiao, Leann Wei

This wellness app targets individuals who are looking for support during difficult times and presents the reasons to skip smudging and embrace alternatives such as breathing and other mindfulness exercises. The app features alternative ways to handle stress, anxiety, sleep and growth – and explains that burning sage is “not magic.”

Designed in an Art Nouveau style, six posters depict soothing imagery and text encouraging readers to pass on white sage and instead download the app. A series of posters can be positioned in a guerrilla-style campaign presenting a street-level appeal that will spark curiosity to learn more. The flourished design can be applied to merchandise such as tote bags.

close

close

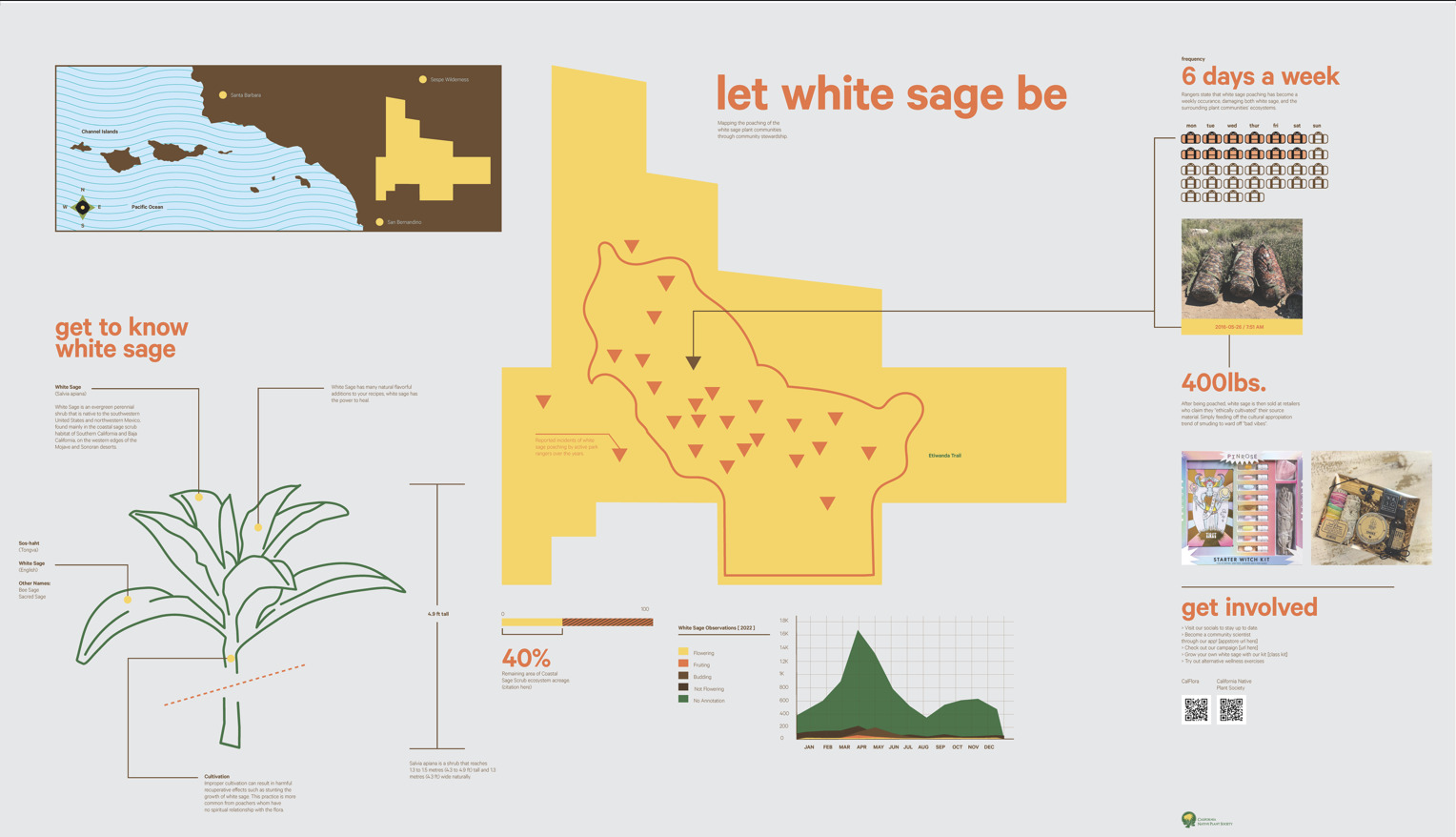

Mapping Plant Communities

Read moreLeonel Guardado, Jamil Watson

To visually understand the global implications of white sage poaching, the project creates a map noting the generalized location of where the plant grows – and the countries that have the highest demand for it. The disparity is dramatic. As a tool to enact policy changes and awareness, the map also features educational components, facts about sage, the indigenous connection to it, and ways to combat the misappropriation.

In addition, this project envisions a digital map app version of where (generally) sage is found locally. If an individual sees poachers or development threatening sage communities, they can send a photo notification that will appear on the map with a time stamp. This map can be connected with CalFlora to help spread awareness of the issue and create creditability with the project.

close

close

Bringing Native Plants Back to an Urban Landscape: Reframing Grand Park

Read moreFernando Vazquez, Yerim Shin, Kyran Knauf

To introduce the public to how native plants have a place in a modern urban landscape, this project reimagines a section of downtown Los Angeles’ Grand Park featuring a variety of native plants in the existing garden space. Using a blueprint of the current garden, these new plants provide experiences that are sensory and visual – along with historically affirming.

Plants will be arranged in sectional zones that correspond to planting conditions and needs. Careful attention is given to bringing plants that grow well together in containers. Also, the design envisions a plant’s seasonal cycles – many natives go dormant in summer – so there is always something of interest growing and/or blooming.

A transportable exhibition installation can be placed in various areas of the park; this modular arrangement of accessible circular bench seating allows for more interaction between people and plants. The accessible exhibition displays QR codes and will have plants growing on top of a shade protector. Surrounding the area will be panels with infographics and information on native plants and indigenous peoples.

close

close

White Sage Protectors

Read moreMegan Pantiskas

To disrupt the illegal white sage trade, this campaign encourages consumers to avoid purchasing poached white sage, by offering resources so store owners can be educated about true ethically based products and become better native plant advocates. A suggested script for store owners and an informational flyer introduce the reality of the sage bundles that are often for sale in these wellness-themed stores. Once a store owner agrees not to support and sell poached sage, they will receive a White Sage Protector Sticker which they can proudly display on their window.

Digital resources will make it easy for owners to include their status via their social media posts. Influencers – especially those in wellness, New Age, and Wiccan communities – will give their approval of the store. Once enough stores sign onto the program, a map of approved stores can be created and circulated.