Never Again 9066: Artists and Designers Against Asian Violence

This Designmatters studio in the Spring of 2023, invited transdisciplinary students to study the unconstitutional incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, known as Executive Order 9066.

Students were tasked with the challenge to use their technical skills as artists and designers to develop political education materials that inform and invite critical discussion around the topic. Students turned their immersive research – that included field trips, historical discoveries and presentations from scholars, artists and a surviving concentration camp inmate – into visually dynamic artwork, engaging educational materials and a public display that authentically portrayed the past but also connected that civil liberties issue to the present.

This transdisciplinary studio was supported by funding provided by the State of California through the California Civil Liberties program, administered by the California State Library. The purpose of the California Civil Liberties Public Education Act is to sponsor public educational activities and the development of educational materials to ensure that the events surrounding the exclusion, forced removal, and internment of citizens and permanent residents of Japanese ancestry will be remembered, and so that the causes and circumstances of this and similar events may be illuminated and understood.

From the Class

Faculty & Partners

Clement Hanami is a Japanese American artist and native Californian. His mother was a hibakusha, or atomic bomb survivor; his father a World War II evacuee. Hanami serves as Vice President of Exhibitions and Art Director at JANM, where he has worked since 1992. He is responsible for the design, installation, fabrication and maintenance of the Museum’s major exhibits. Hanami co-designed the Museum’s core historical exhibit Common Ground: The Heart of Community, which has been seen by over one million visitors to date, and co-managed the collaborative Finding Family Stories project. He recently curated Instructions to All Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066. Hanami has an M.F.A. in studio art from UCLA and 30+ years of experience in working in civil rights.

Bianca Nozaki-Nasser is a Los Angeles-/Tongva land-based multimedia artist, educator, and organizer. For the past decade, her work has focused on the relationships between creative media, digital strategy, and cultural organizing. Nozaki-Nasser has spent the last five years working as the Strategy & Creative Director at 18MR, a national Asian American advocacy organization at which she develops grassroots campaigns that mobilize its 170,000+ members around social issues. Earlier, Nozaki-Nasser developed a social data-based cultural trend forecasting tool. Born to a Syrian-Lebanese father and Japanese American mother, Nozaki-Nasser’s creative practice draws on her own experience navigating familial legacy, transnational culture, material language, and the politics of artifacts. Nozaki-Nasser cofounded the Antiracist Classroom, an initiative to address White supremacy in design education and practice, and was a core organizer with amwa.work, a Los Angeles-based collective of Asian American femme and/or non-binary artists. She earned her M.F.A. in media design practices at ArtCenter and her B.A. in communication at the University of Southern California.

“I identify as both Japanese and American. Since my grandfather was incarcerated at Manzanar when he was a little boy, I wanted to learn more. I wanted my project to honor that history, to keep that legacy alive.”

– Emily Chen, Student

The Japanese American National Museum

The mission of the Japanese American National Museum is to promote understanding and appreciation of America’s ethnic and cultural diversity by sharing the Japanese American experience. As the national repository of Japanese American history, JANM creates groundbreaking historical and arts exhibitions, educational public programs, award-winning documentaries, and innovative curriculum that illuminate the stories and the rich cultural heritage of people of Japanese ancestry in the United States. JANM also speaks out when diversity, individual dignity and social justice are undermined, vigilantly sharing the hard-fought lessons accrued from this history. Its purpose is to transform lives, create a more just America and, ultimately, a better world.

The Challenge

Today, to responsibly and thoughtfully engage with history, it must be understood in relationship to larger systems, stories, and perspectives. Students were tasked with translating a historical component of Japanese Incarceration into a visual map format. Students were asked to create educational materials that used visual systems to address at least two of the following areas: gaps in historical knowledge and analysis, misrepresentation through limited narratives, isolated histories, and notification/news cycle fatigue.

Project Brief

In this Designmatters class, students delved into the unconstitutional incarceration of Japanese Americans – Executive Order 9066 – during World War II.

The work was created and presented in a process as product format – students shared their journey with engaging and learning about the issue through an art and design- based practices.

The goals of the studio were:

- Create a space for students to join their creative skills with social justice movements.

- Contextualize and connect Asian American history and experience to other communities to build solidarity and power.

- Build New Narratives that include perspectives that are routinely overlooked or trivialized.

Over the course of the term students learned how to apply historical analysis and values driven impact campaigns to their creative process. This studio provided students with hands-on experience while creating a space for them to develop their unique perspective as artists and designers.

Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II

When Japan dropped bombs on Pearl Harbor signaling a new chapter in the war, the U.S. Government feared many Japanese Americans would pledge loyalty to Japan and secretly work to bring down America.

President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which sent more than 120,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry to 10 concentration camps. Anyone who was at least 1/16th Japanese was evacuated – that included 17,000 children and several thousand elderly and disabled residents. People were forcibly removed from their homes – often with little notice – and could only take what they could carry.

“The United States government justified their actions as a military necessity, viewing those of Japanese ancestry as a threat to national security despite there being no evidence to suggest this.” (THEY CALLED US ENEMY TEACHER’S GUIDE 2019) This mass incarceration was fueled by Anti-Asian racism, xenophobia, and war hysteria. National Security was cited as justification for this policy although it directly violated the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans.

“In this class we ask where is everyone coming from? Some people are right there on the precipice and then fall right into place, others, because they feel like outsiders, have a little border. Our goal as teaching from an insider perspective is to open the doors and let people in and find that allyship.”

– Clement Hanami, Faculty

The camps were in isolated areas, mainly in the Western United States. For years, many Japanese Americans lived in harsh, overcrowded conditions, surrounded by barbed wire fences and armed guards.

Following the culmination of the war, President Harry Truman ended the camps in 1945; the last Japanese concentration camp closed in March of 1946. In the, “1960s activists linked the wartime detention camps to contemporary racist and colonial policies. In the late 1970s three organizations pursued redress in court and in Congress, culminating in the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 , providing a national apology and individual payments of $20,000 to surviving detainees.” Executive Order 9066 was not officially repealed until 1976.

Research

Faculty, Bianca and Clement, were intentional in their class development, and began the studio by grounding students in both historical and critical frameworks. The studio began with four weeks of intensive research and discussions.

These first four weeks included historical research, field trips and testimonies from scholars, artists and surviving concentration camp inmates. Throughout the course of the studio, students engaged in lively classroom discussions, but homework – readings, YouTube talks, etc. – helped students go deeper into the topic and allowed time self-reflection on their own experiences and beliefs.

It is critically important to acknowledge the political climate during the time this studio took place. Many assignments and readings discussed how legacies of yellow peril and Anti-Asian violence persist in American today. Since 2020 there has been a rise in the visibility of Anti-Asian violence, including multiple racist mass murders, notably the shootings that targeted Asian women spa workers in Atlanta and Sikh worshippers in Indianapolis, respectively.

As a predominantly Asian and Asian American class, it was important to directly address and discuss student’s own experiences and relationship to these topics. As violence towards Asian people and state violence that continue to impact many Americans, especially Black people and People of Color, it is critical to note that these students were not designers relating to historically excluded groups, but rather many of them are a part of affected communities.

Students, through weekly blog posts, described what they learned, how their personal values correspond, and how their art could be infused with social justice concepts.

Clement guided students through significant moments in history as well as invited community guests to dive deeper into specific areas. To further illuminate the topic, students heard in-class speakers that offered unique points of view: Brian Niija, curator from the Japanese American National Museum, and Kris Kuramitsu who curated “Voice a Wild Dream” at Occidental College about art and community service in Asian American collectives.

During the research phase, Bianca also introduced students to frameworks outlined by the Design Justice Movement. “Design justice rethinks design processes, centers people who are normally marginalized by design, and uses collaborative, creative practices to address the deepest challenges our communities face.”

“Spaces have history. How do we remember things that are traumatic?”

– Clement Hanami, Faculty

Students also investigated Media Based Organizing, a collaborative process that creatively incorporates media, art and technology as a tool for individuals/communities to advocate for actions or solutions. For example, students studied the multimedia project “Unmasking Yellow Peril” which invited Asian-Americans to tell their own stories of immigration, discrimination, and resilience. Recent violent attacks against Asian Americans presented real-life incidents that could help shape students’ design thinking.

Preparing for their research, students learned how asking the right questions can provide opportunities for expressive storytelling and allow for artistic representation that is not just decorative, but rather, meaningful in content and messaging.

The class discussed defining a Theory of Change which outlines the process of using design for social justice. A series of questions can direct students to be honest and specific about their intentions. “Why am I doing this?” “Who benefits from this?” “What is the impact I want by doing this?” “Whose worlds am I building?” “Who is harmed or possibly put at risk?”

Bianca introduced a Values, Problem, Response and Action (VPRA) framework, adapted from The Opportunity Agenda’s VPRA framework, to offer students a new way to consider developing messaging. The process stresses that being as specific as possible will guide the design direction: present one problem, one response, one action.

Values, Problem, Response and Action (VPRA).

Values: Start with values, share a positive vision, be proactive

Problem: Frame the issue, name the target, don’t overwhelm with details.

Response: Provide a clear theory of change and a positive response. It is not a solution.

Action: Offer one call to action to solve problem.

Using their research, personal experiences, and own design-sensibilities, ArtCenter students developed compelling visual artworks that featured educational components of Japanese American history which could connect thematically to civil liberty issues of the present. Students began to untangle the many systems and factors that created continued histories of persecution, discrimination, and violence. However, as they deepened their research students also began to find often overlooked moments of resistance in the ways that the Japanese preserved their cultural rituals and the arts while incarcerated.

All during the research phase, students were continually reminded that design without content and strategy is just decoration.

Historical Connections, Spaces in Time

Two field trips were especially poignant for the students, giving them an in-person experience, which helped focus their projects.

A curated visit to the Japanese American National Museum in downtown Los Angeles provided historical voices, an overview of the Japanese American experience and a link to important cultural moments, traditions and more.

“How do we remember?” was a recurring theme of the trip where students examined how the museum presented history through advanced technologies and updated reinterpretations. In one exhibit, students viewed a large book that lists 125,000 names of those incarcerated; visitors are invited to say that name out loud which gives a deeper psychological connection to the past.

Students toured other exhibits and viewed a short documentary “Pilgrimage” about young Japanese Americans re-embracing Manzanar in the late 1960s that spurred annual pilgrimages as an act of remembrance and solidarity. Students had the chance to virtually talk with the film’s creator Tadashi Nakamura; he described how “no one wanted to talk about” incarceration camps but once young Japanese Americans discovered the ruins of these camps, they felt compelled to share the stories. “There is a burden when you have knowledge of your history; now there is the responsibility to stand up,” he told them.

Nakamura encouraged students to discover “new angles that haven’t yet been told before” as they examined how they could turn relationships and narratives into a visual form. “Understand your role and don’t exploit their stories, but become an ally.”

Spaces have history in it, they learned.

This video set the stage for the student’s upcoming field trip to Manzanar where they toured the site, spent time digesting information, asked questions, and above all, listened to the historical facts and personal stories this camp offered. Walking in the dust of where so many people were imprisoned was a sobering and powerful experience for the students.

Manzanar’s interpretative signage and interactive exhibits provided the students with many options to explore in their own projects – but they witnessed the humanity of what Manzanar represents to the world.

In addition to these experiences, students also had an enlightening session when camp survivor Mas Yamashita visited the classroom to share his experience as a child in a concentration camp. Here was a first-hand account of what life was like for Japanese Americans. Students were respectful and grateful for Yamashita’s story, asking questions which helped them get a full-rounded view of camp life.

Project Development

After weeks of researching Japanese American Incarceration, studying components of radical cartographies, and discussions on material language students were asked to map an issue area from their research. Students needed to represent many components, relationships, and narratives that create the larger narratives of history in a visual form. Students explored different mediums ranging from drawing, graphic design, sculpture, and painting to learn either something new about the subject or learn something about how to represent that subject in a completely new way, or both.

Informed by research, data, stories and history, students began prepping for “mapping the issue” a contextualization of a specific aspect of Asian American history and experience which could resonate with the viewer.

Students examined how other artists such as Terry Boddie, Keith Walsh and Faith Ringgold how they define their culture through physical objects, resources, and spaces, i.e. the material language.

As they worked on their map projects students were encouragedasked to revise their VPRA work. As they began to share their drafts students were encouraged : “In one sentence, tell us what story you are telling with your project.

“I’m so happy to see so much of the students in their own work, their relationship to the subject, their family histories, the questions there were interested in. Their work reflects sensitivity to the topic, but also celebrates the dignity and humanity of these stories.”

– Bianca Nozaki-Nasser, Faculty

At mid-term, students shared their maps which highlighted people, geography, policies, social/political/economic issue and more. Students also explained a bit of their process through previous drafts and incarnations – and how these steps helped them move forward to this “finished piece.”

Artist statements/personal reflections accompanied each piece of artwork that ranged from posters, infographics, sculptures, etc. Visual pieces featured a variety of topics from reparations, censorship, language, beauty and how Asian Americans are not a monolith.

As they presented their work, students explained their process and how they arrived at this conclusion. Instructors and classmates guided student presenters on what elements were most powerful and how to tweak their creation. Students were supportive of one another, offering suggesting and brainstorming for each other. “What message are you trying to convey?” was a common question.

After mid-term, students continued to refine their works; others backed up and took slightly different directions, while other embarked into new territories. All students, however, were guided by instructors who kept encouraging and reiterating concepts and directional methods.

As they worked toward the final presentation, students prepared a written project statement, offered a selection of prompts for further reflection and a breakdown of their VPRA (Value, Problem, Response and Action) thinking.

Projects Outcomes

Project outcomes were accompanied by written statements, an intended target audience and answering a series of questions based on the VPR A model. “Why should your audience care?” Describe the problem, what kind of response you want, and what kind of concrete actions your audience can do.

Prior to their final presentation, students created a public installation by choosing an iteration design to be enlarged and then displayed on a wall along Raymond Avenue. These orange and white banners contained images or words that were a critical part of their project/power, often highlighting a theme, moment, narrative or concept.

Outcomes

close

close

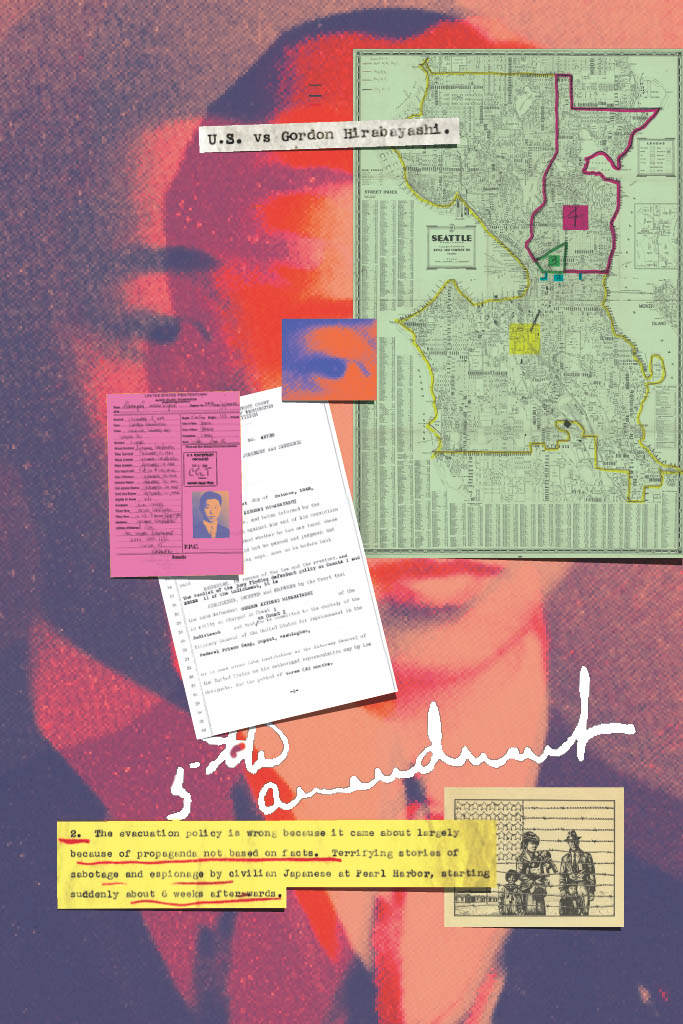

US vs. Gordon Hirabayashi

Read moreNaYoung Kwon

This poster depicts an image and elements from the life of Gordon Hirabayshi who became a hero in the Japanese-American community for his refusal to go to the concentration camps, turning himself in to the FBI. The subsequent court battle that ensued lasted decades after the war was over.

This scavenger-hunt type of collage directs viewers first to the bright yellow section highlighting the Fifth Amendment. File documents, prison records, street maps and other elements are pieces of a man whose life became entangled in the fight for freedom, and his loss of identity as a Japanese American. A single eye is prominently placed in the middle.

close

close

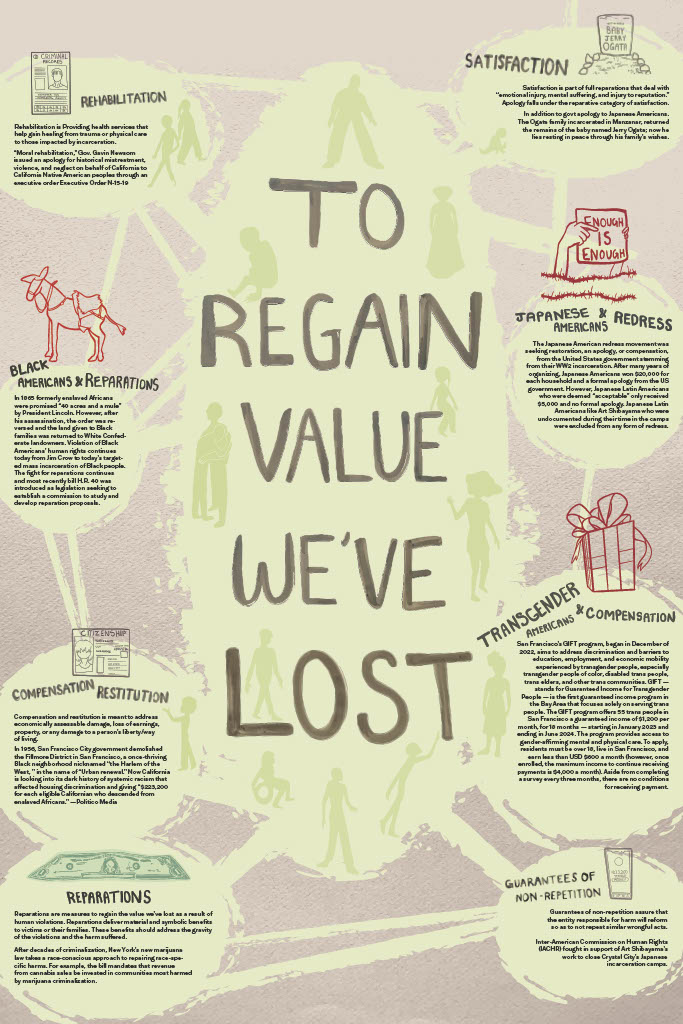

Art Shibayama and the Branches of Reparation

Read moreNaomi Nakamura

This zine encapsulates stories of Japanese/Latinos into the story of Isamu Carlos Arturo “Art” Shibayama who, as a young boy, was kidnapped from his Peruvian home in 1944 and imprisoned at Crystal City, Texas for two and a half years. Shibayama was one of thousands of Japanese Latinos who were deported by the United States government. Upon release, many Latino Japanese individuals and families were sent to Japan, a country they have never visited lived in or visited. The Shibayama family traveled from Texas to New Jersey and then to Chicago.

In 1993, most eligible Japanese Americans were issued an apology and financial reparations from the government, however, Japanese Latinos were denied similar treatment citing their illegal alien status during the War. The redress proposal continues to be denied to this day.

The zine uses illustrations and actual quotes from Shibayama to tell the story of his experiences. Once opened up fully, the backside displays in a graphic overview describing five categories of reparations with informational text and recent events linked to specific communities (Black, gay, etc.) that are fighting for justice and closure.

close

close

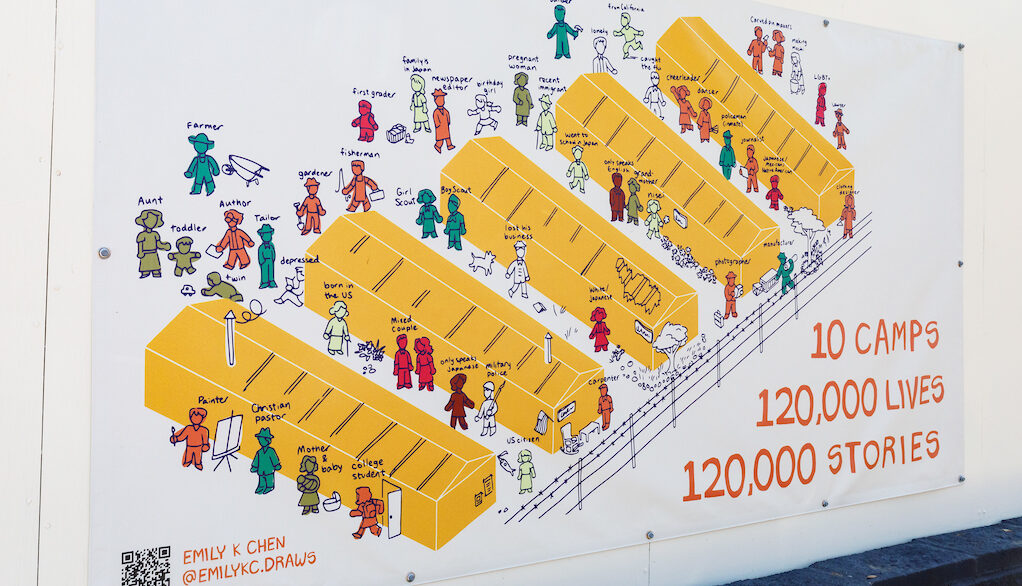

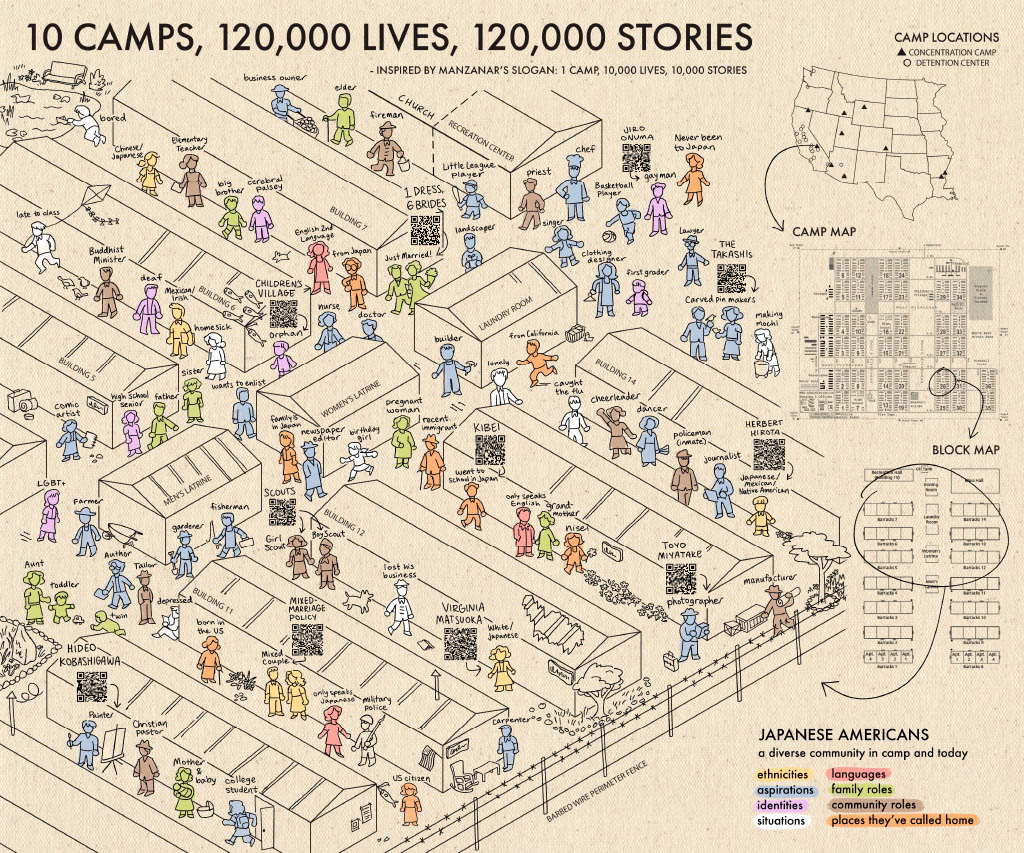

10 Camps, 12,000 Lives, 120,000 Stories

Read moreEmily Chen

To depict the rich diversity of lives in the concentration camps, this map features a hand drawn section of barracks in one camp block with figures walking, playing, gardening and other lively activities that inmates engaged at while at the camps.

Figures are color coded to show various aspects of lives that were imprisoned: by ethnicity, occupation, language spoken, family roles, ages, sexuality and more. The drawings are inspired by Richard Scarry’s Busy Town children’s books.

QR codes are located near some of the figures. Viewers can scan their phones and be sent to a webpage where they can read more about this particular person, couple or family.

For perspective, the far side of the map shows how this one block fits into the entire camp schematic, and then where in the United States all 10 concentration camps were located.

close

close

Significance of the Model Minority Myth and the Abolition Movement Demonstrated Through the Events of Executive Order 9066

Read moreRen Bennett

Viewers can interact with this 3-D tall cylinder sculpture by placing a marble which descends through a series of ramps, with physical stops at written plaques describing specific facts how Executive Order 9066 purposefully and unfairly treated Japanese Americans. The U.S. government overreacts to a terrorist threat with a larger pattern of relocation, unpaid labor and neglect.

The sculpture features a tree on top and ramps give the illusion of roots which illustrate how white supremacy is deeply rooted into the American psyche and continues to flourish.

close

close

Acts and Aesthetics of Resilience and Resistance

Read moreNaomi Kurihara

A poster and small booklet describe how inmates at the concentration camps used found materials to create beautiful jewelry and gift items, often re-discovering their deep Japanese heritage.

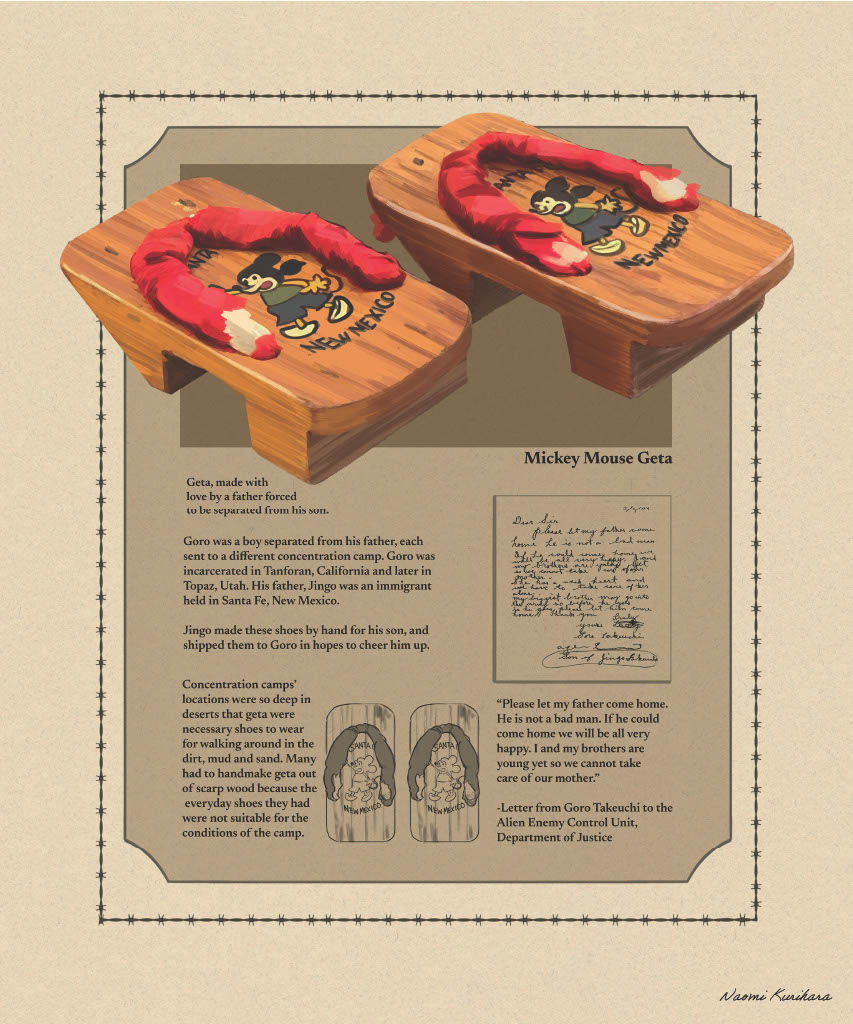

The poster, encircled with barb wire imagery, shows a pair of traditional Japanese geto shoes that were made from scrap wood and adorned with Mickey Mouse drawings. These shoes are an actual gift from a father to his son (who lived in a different camp) who wanted to cheer up his son – but the shoes also proved functional in the dry sandy environment. The poster also reproduces a letter the son wrote to the government asking them to release his father because “he is not a bad man.”

The illustrated booklet shows handmade objects of real pieces created in concentration camps. The ingenuity of people to take spent sunflower seed shells and turn them into a brooch or a create a ring made from a peach pit is depicted in four posters. At the end of the war, inmates were often embarrassed by these homemade items and threw them away.

close

close

Sanctioned Erasure

Read moreNeko Ohnsman

The poster text describes the history of language as a form of cultural identity, and explains the tragic loss of culture when language is stifled.

Inspired by the story of camp survivors Mas Yamashita and John Tateishi, this text book style poster (an English and Japanese version) features an illustration of Mas and his quotes about not wanting to speak/read the Japanese language after being released from the camp – and growing up, being ashamed of their culture.

Through talking bubbles, a trio of illustrated heads also explains reasons

(“for the children,” etc.) for turning away from their language and culture.

The top of the text book page is a muted red, white and blue American flag. A prompt box at the bottom suggests discussion points. Using the style of a textbook gives the poster a neutral and reliable appearance even though textbooks in the past have been sources of cultural biases.

close

close

Tanforan Art School

Read moreConnor Simpson

This art map depicts the influence of the Tanforan Art School which was started at the Tanforan Camp by artist Chiura Obata and his artist friends to help remind inmates of the beauty that is in the world. The school later moved to Topaz, Utah. The school taught more than 600 students from ages 6-70 where they could learn and practice figure drawing, still life, anatomy and commercial art.

This oil painting on a large piece of wood is a combination of imagery, photos, people and their art along with abstract flourishes and direction. Artwork created by the founders of the school is featured.

close

close

Woodcarving Creation in Concentration Camps

Read moreHaozhou Lin

Examining the symbolism of a bird in flight, this map of woodcarvings show how those imprisoned in the camp used art as a way to escape. It’s believed these eight art pieces are from students of woodcarving instructor Yutaka Suzuki.

After the war, the woodcarvings were scattered across the country. This map, however, combines parts of all these different wood carvings to create one new image.