Living Home India Documentary

A short documentary that follows a team of Art Center students as they research the housing needs of low- and middle-income families in India.

A multi-disciplinary team spent the Summer 2012 term investigating the living needs of low-income housing dwellers in India, and then building furniture prototypes for use in the high quality, low-cost housing championed by social entrepreneurship nonprofit Ashoka.

In India, where the program has really shown success in delivery of homes, we believe that creating an eco-system, which would include furniture, sustainable energy and better design thinking is key. Art Center is a key strategic partner to frame the right design thinking for furniture for such homes—this is central to establishing the right synapses between the needs of the community to the best affordable furniture design solutions.” – Vishnu Swaminathan , Program Director, Housing for All, Ashoka

Over one billion people—32 percent of the global urban population—live in urban slums in emerging countries, with 500,000 more joining them each week. Relatively poor nations will build the equivalent of a city of more than one million people each week for the next 45 years. Embedded in such migration patterns and population growth implications is the critical need for affordable and safe housing. In 2008, the nonprofit Ashoka launched its Housing For All India initiative, an innovative public-private sector alliance that puts local social entrepreneurs from several key cities in India at the helm of driving affordable and environmentally responsible housing development for India’s growing lower-income population. Ashoka estimates this emerging market at more than 130 million people, accounting for more than $250 billion (U.S. dollars). Looking further ahead, the potential need points to a looming megatrend. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, an estimated 590 million people will live in urban areas of India by the year 2030–nearly twice the population of the United States today. For millions in India’s poor urban areas, a “home” means one room. In order to discover design options for creating furnishing specific to the needs of urban Indian communities, Art Center and Ashoka teamed up to explore the creation of sustainable, cost-efficient, and ready-to-market furniture prototypes.

During the Summer 2012 term, students in the transdisciplinary Living Home: Indiacourse investigated the living needs of the low-income housing dweller in India. Due to the reduced scale and high occupancy rate of their housing units, the students were tasked with creating furniture prototypes that are reduced in scale, transformable and which apply themselves in new and innovative ways. The students were asked to incorporate environmentally responsible designs and to develop the furniture in close collaboration with community stakeholders and local craftspeople in India. Ashoka played a key role in facilitating the student’s collaboration with local and regional constituents, and the activity sites were strategically selected to maximize Ashoka’s existing infrastructure of partnerships.

Whenever we design, we’re always thinking about the people themselves. Is our work really addressing the people that are going to buy it? What do they want from it? What do they need from it? What do they need to feel from it?

– David Mocarski, Chair, Environmental Design

The overall goal? For Art Center students to apply “fresh eyes” to India’s current issues, needs and concerns and offer innovative solutions for products, materials and manufacturing for a low-income user base estimated at 130 million individuals.

The design brief of the project called for a paramount understanding of the potential Indian consumers of these furnishings. The studio was designed with a field research trip to Bangalore (the Ashoka India base) that was envisioned to provide the team with in-depth immersion of India’s low-income housing needs as well as a first hand experience of cultural and aspirational drivers of this population. Pre-Field: Before the field trip, an extensive day-long workshop led by Marisa Cohn, a Ph.D. Candidate at UC Irvine’s Department of Informatics well versed in design ethnography methods, helped prepare the students with a hands-on workshop on best practices. This session addressed the complexities of conducting ethnographic research alongside design practice, emphasizing responsible research methods and culturally-aware approaches to ethnographic writing. In addition to this workshop, the design faculty developed a series of method cards to assist students with their research in the field. Proposing activities ranging from cataloging a “day in the life” of individuals and families to visiting local markets and shops, the cards also presented possible methodologies along with qualitative and quantitative questions to help students think comprehensively about Indian users, craftspeople, and manufacturers. Download1

Formulate how you want to move forward and reach out. That’s part of the design process too. Design is 20% and it’s the easiest part. The other 80% is, ‘Okay, what now? What do we do with this?’ That’s the strategy part. How do we take good design and what do we do with it? It doesn’t automatically fall into your lap.

– Cory Grosser, Instructor, Environmental Design

Studio:

After paying particularly close attention to how the people they encountered in Bangalore used design to express their own world views, the students embarked on an extended conceptualization process upon their return to Art Center. Many continued their research on India in the library and on the web, exploring topics from economics and craft traditions to education policy and parenting. These continuing paths of inquiry were woven into sketches, diagrams, and models designed to present relevant solutions to the unique living needs of their users. By the end of the course, the students had built full-size working prototypes that incorporated their investigation into their client’s culture and addressed manufacturing feasibilities.

The student produced individual projects that were broken into five main categories that some projects overlapped. These were identified as representative of unique opportunity in the furniture market for this target population: Children and Education; System Design; Partition and Storage; Convertible; and Seating.

close

close

Alexandra Yee

This is an affordable, lightweight, flat-pack desk and seat that sparks imagination by providing children with a sense of comfort and personal space as they grow. Through simple folds of the laminated cardboard, and the help of a parent, a child can have endless adventures with Chota Motu. It transforms from an elephant, encouraging studying or adventure play, to a comfy floor seat that creates an enclosed space where the child can lounge.

close

close

Kimberly Chow

Inspired by the high esteem in which Indian families held education, Kimberly Chow designed the Launchpad Study Kit, a folding desk for children designed to optimize positive study habits in the home by providing a work surface, proper lighting, a personal space and an excitement for learning. The desk features two modes, “Study Mode” and “Storage Mode” and includes features such as: a minimal footprint when packed away; a rechargeable light that lets kids study through frequent blackouts; and pencil cases, folders and elastic straps to help the child organize his personal belongings.

close

close

Alex Cabunoc

This is a convertible storage and room divider that addresses the challenges of living in a small space. Cabunoc noticed that in many Indian homes the living room served multiple purposes throughout the day, including sleeping, entertaining, eating, studying and relaxing. In its closed position, Asana Wall is a small decorative storage cabinet whose vertical panel offers a splash of color and whose lower cabinet provides storage for shoes and other small items. In its open position, it fans open to become a large room divider that allows for new areas to be created for specific purposes.

close

close

Jen Kuca

While in India, Kuca noticed that if you ask a group of individuals one question three times in a row, you’ll receive three different answers. Each new answer would contradict the previous answer, yet all three answers were correct. This made her wonder how to design for a world where so many possibilities abound. Inspired by the traditional Thaali meal in which individuals are given several dishes at once and then go on to create their own mixes, Kuca became interested in designing not furniture, but a system of furniture components that would allow individuals to inject their own personalities, beliefs and aesthetics into their furniture. The system—which would consist of only four components—would allow individuals to inject their own personalities into their furniture and allow an object like a child’s chair or a coffee table to be easily transformed into into a tall chair or a sofa. Kuca also envisioned that these components could be sold directly outside of new apartment complexes in mobile rickshaw-inspired stores, and turned into furniture by a workforce who would assemble the components for a fee.

close

close

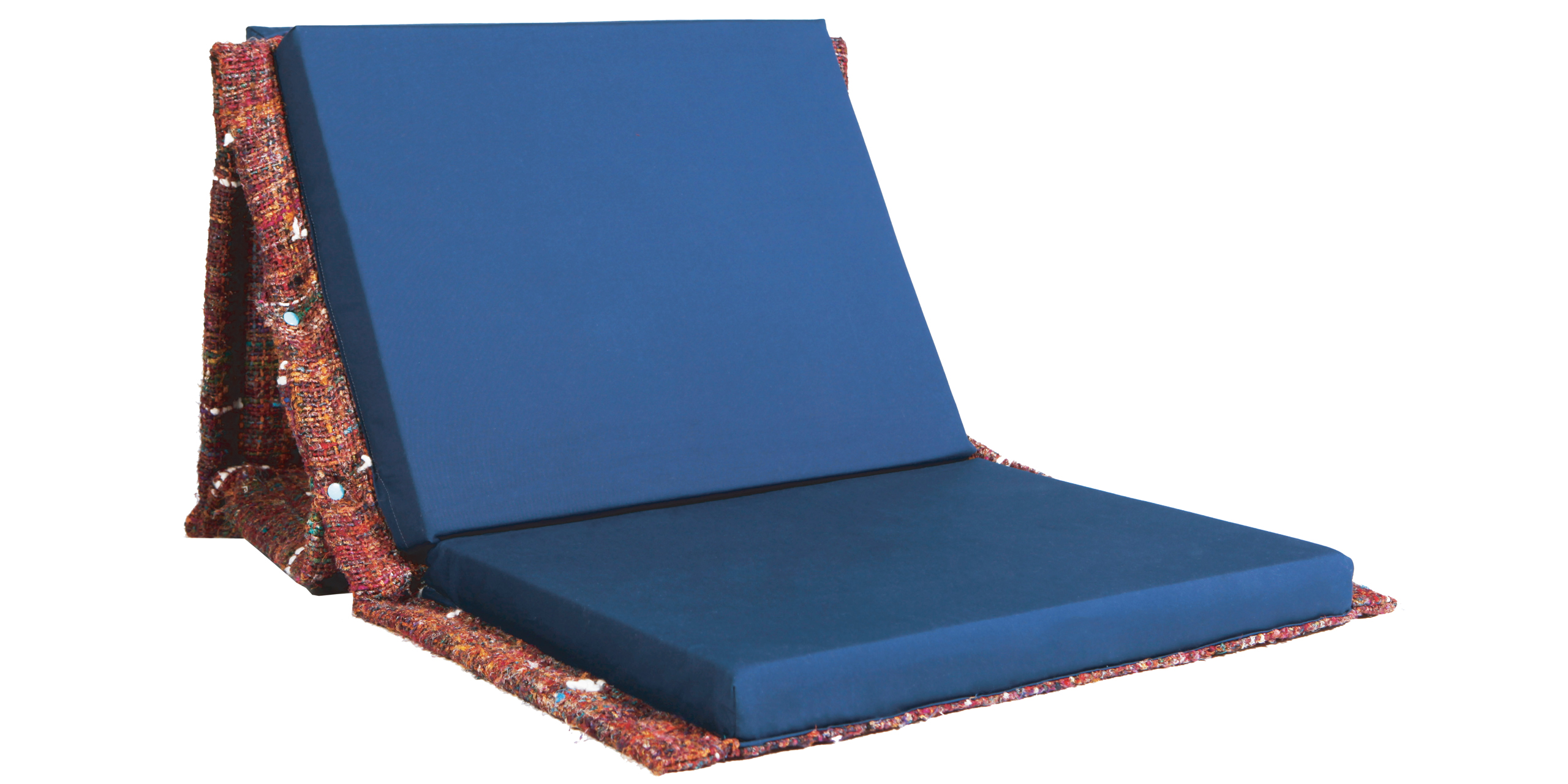

Stella Lee

Inspired by her research on small single family living spaces, Lee designed, an all-in-one folding mat which can be modified to adapt to the changing functions of a space. The spaces she observed in India ranged from 300 to 400 square feet, were usually shared by three to five family members, and had to function as a study room, dining room, family room or a bedroom. Lee’s Modi Mat can be folded and unfolded into a number of different positions, including completely flat for sleeping, a lounge position for reading or relaxation, and a dual chair to accommodate two individuals. It can also be snapped shut and includes straps for maximum mobility.

close

close

Esmerelda Rennick

Believing that families transitioning from the slums into low-income housing developments are taking a large step into a global society, wanted to design a piece of furniture that would signal to the community that they’re moving up the social ladder. Her design is an air-blown plastic stackable chair that makes accommodating guests easy and affordable. Designed to take up less space than the current plastic chairs on the market, Aditi provides an elegant and comfortable place to rest and includes a built in cup holder where guests can rest a hot cup of chai tea.

close

close

Cora Neil

Inspired by the way Indian women entertain in the home—female guests gather and socialize in the bedroom, while men entertain in the living room—Neil designed this transformable piece of folding furniture that allows the bedroom to feel like an entertaining space while maintaining its bedroom functions. During her visit, Neil heard several times that a sofa bed would be a valuable piece of furniture, but the expense of owning one made it out of reach for many. By reinterpreting the sofa bed—removing complicated and expensive hardware and keeping in mind local materials and fabrication capabilities—the Daydreamer offers an affordable, space saving sofa during the day and a raised bed at night.

close

close

Ji A You

You also found in her research that a sofa bed was much desired, but the complexity of the hardware meant they couldn’t be manufactured locally and were thus expensive. As a response, Repose is a petite and colorful modular sofa-bed system for individuals living in smaller spaces. In contrast to Neil’s Daydreamer, You’s Repose is a primarily a sofa meant for the living room. A sofa, which, with one simple movement, can be extended into a sofa with a side table for entertaining guests during teatime, or, by adding a mattress extension, turns into a twin-sized bed. Except for the mattress and pillows, every element of the elegant Repose can be made out of a single 4”x8” sheet of plywood.

close

close

Carlos Vides

Something that immediately struck Vides about India was the modern appearance of the new low-income housing developments. At that point he decided that whatever he set out to design had to be something he himself would want to buy. It would also need to be affordable, but stylish and well made. Looking at Indian furniture design, be discovered the char pad, a traditional outdoors daybed. Vides heard from many individuals that they wanted both a couch and a place to sleep a night so he created Charpad by attaching Velcro straps to four pre-existing mattresses and rolling and arranging them atop a lightweight wooden frame. The end result is a simple, elegant daybed that easily converts into sleeping arrangements for four individuals.

Both the design-centric research and development process of the Living Home India studio and its outcomes represent an important initial collaboration and knowledge-exchange between Designmatters and Ashoka. The design team is currently assessing next steps to bring these designs to fruition within the framework of Housing for All (HFA) India’s ongoing efforts to lead market-based models that provide home improvement and new homes services at quality and affordable prices.