Meta-Museum: Re-Contextualization of Institutional Collections

- Public Policy

- Social Justice

This Designmatters studio challenged ArtCenter graduate and undergraduate students to explore the current state of museums and other institutions as they recontextualize their collections to present a more honest representation of history and culture that is not entangled in racism, colonialism, homophobia, sexism and other forms of oppression.

Students were tasked with delving into the details of an exhibit showcasing African peoples opened to the public in the 1960s. Students reframed various aspects of exhibit with cost-effective measures that included new technologies, visual layering and updated commentary offers visitors a more complete view of the history of exhibit along with exploring 1960s attitudes and the ever-changing role of museums in society.

Project Brief

Tackling big questions about the current role of museums in society, this Designmatters studio challenged graduate and undergraduate students to learn, first-hand, the ways that today’s institutions are re-contextualizing their collections with the hopes of presenting a more honest representation of history and art that is not entangled in racism, colonialism, homophobia, sexism and other forms of inequity.

Students reimagined an exhibit showcasing African peoples that opened in the 1960s. They crafted prototypes to help visitors understand the complexities involved in not just the subject matter but also how a particular exhibit was originally presented in that era. Students reframed their exhibit with cost-effective strategies that employed cutting-edge technologies, visual layers, and updated commentary along with curated informational slices that would provide a new, and more profound, user experience.

“I see myself in the future in these kinds of projects of decolonization and social justice; I’ve been researching my own ancestry.”

David Espinosa Perez, student (Illustration with Designmatter Minor in Social Innovation)

Re-Contextualization of Museums and Institutions of Collections

The rise of museums and institutions of collections can be traced to the Age of Exploration from the 1600-the 1700s, which witnessed numerous expeditions sailing the world in search of new plants, animals ,and peoples. Museums were established to share these “wonders of the world,” much like how World’s Fairs were created to offer the public a chance to “travel the world without traveling.”

Today, museums are faced with the challenge of how to disengage with their past while acknowledging its inequities. Many institutions are embarking on recontextualizing both their brand and exhibits to shine a light on their historic entanglements with racism, colonialism, homophobia ,and other forms of oppression. Crafting these new narratives can be awkward, especially when the museum itself, possibly a venerated institution for decades, can now be viewed as an artifact.

Museum leadership across the country is at a crucial juncture; balancing how problematic histories can be made visible to the public – and will such a change adequately address issues of justice? Crafting new narratives today often involves accessing current technology with an engaging commentary which can provide a non-biased representation of the past. A goal is to offer the public a more meaningful and thoughtful visit that can spur conversation as well as a deeper sense of this place in history.

“Looking at all the students’ projects, every single team had a totally unique perspective, had a different approach. And while this studio had a broad brief, the students made a brief for their own teams. That specific point of view, that message and approach. Each team had to come up with its own brief, the design perspective and design language. I am so proud to see that in each of these final projects.”

Elise Co (Faculty, Interaction Design)

Research and Project Development

At the online kick-off session, students learned the studio will have two areas of focus: the first half would involve deeply understanding the complicated history of museums and the current contemporary issues they face. Weekly reading, writing assignments, and in-class discussions would provide the necessary context that would later inform their design techniques and choices for their final project.

The second half would offer the students a hands-on experience of how best to recontextualize an exhibit from the 1960s involving the people of Africa. Students will examine the contents and come to understand why curators chose certain artifacts, verbiage, etc. Working in teams, students would explore a wide array of solutions that could run from cutting- edge technology to clear and effective signage.

To start the studio, students shared a personal museum memory; these experiences became a jumping-off point for a whole class discussion on how certain aspects of museum design can create long-lasting and noteworthy memories.

Later discussions helped steer the students to the larger concept of how to critically think about and view institutional collections – including why they were first created and what they can be today. Students learned how museums are often the product of imperialism that reflected the attitudes of the day, i.e., racism, sexism, colonialism, etc. Students were taught that a building is not just a building or a collection of objects but it is often a vehicle meant to persuade the masses toward certain attitudes of taste, class, and society.

Students learned ways to use existing exhibits to illustrate various points of view that may not have been included in their original presentation. These methods and strategies can be done effectively within budget restraints and often do not need to remove or remodel an exhibit (which can be costly) but rather focus on how best to incorporate the existing materials with new supplemental information.

Students were asked to think about and share their personal connections to the land they came from and the land their grandparents were born. Was that land ever colonized by others? Who? Are you descendants of those who did the colonizing or who were colonized? This exercise reminded students of the far- reaching implications of colonialism which modified and/or erased existing cultural touchpoints of clothing, diet, language and even names.

“I have been very interested in the topic of decolonization. It was exciting to have the chance to get really deep into the topic. We had to approach it from a design-solution way while re-designing an aspect, learning all the complications that arise and having practical considerations– all at the same time.”

Qianyue Yuwen (Graduate Media Design Practices)

As students examined how other museums are de-colonizing their collections and exhibits, they were challenged to think: How can the voice of the oppressed be heard more in this setting? How can the museum itself be treated as an artifact?

In the following weeks, students read blogs, essays, watched videos about decolonization and researched how to effectively write about Africa and the Black experience. Instructors facilitated lively in-class discussions while students shared personal observations and continued to pose new questions and issues to explore.

Discussions also described how to dissect and present a point-of-view (POV) and how the curator’s intention plays into the overall thinking and implementation. Effective storytelling through technology was a broad topic that students delved into; how to create an honest, understandable narrative yet be true to your POV? How can illustrations, photos, videos, and other visuals “speak for themselves?”

Students chose a exhibit involving the peoples of Africa found in a typical Natural History museum – artifact display, diorama, etc. – which they could transform into a new perspective and new user experience. They examined the current descriptive text, analyzed the contextual text and studied how ancillary objects near an exhibit play into the overall presentation.

Students also considered the display from the point of view of the object as well as how people portrayed in dioramas would feel being represented and exhibited in this current manner. How could that presentation be improved?

While crafting their interventions, students were encouraged to always question how to create an experience that allowed visitors to come to their own conclusions about the exhibit’s objects and depiction of African lives and experiences. Additionally, the understanding that their interventions needed to be affordable invited the students to cast a wide net for creative solutions.

In preparation for the midterm, individual and team assignments became more directed to the actual exhibit methodology: designing an audio tour and wayfinding signage, developing an AR experience, and creating a re-imagined diorama that avoids objectification.

“Teams had a POV statement they reiterated every week which could change. And did. Is this POV represented in the work – or is the work going in a direction that the POV is shifting? They had to do a lot of research that was content-based, learning about a particular history of a particular object, and the cultures that they come from.”

Elizabeth Chin, instructor (Faculty, Humanities and Sciences & Media Design Practices)

Midterm Presentation

Student teams outlined their original concepts and possible directions in short five-minute presentations at the studio midterm; the goal of the presentation was for the students to gauge responses from subject matter experts which would set them on a path toward the final project. Teams were especially interested in discovering how their POV received by a new audience. Was it compelling? Original? Easy-to-understand? Was it narrow and specific enough to merit further development?

Teams explored what elements of their design thinking resonated with an audience.? What elements are engaging? Is there a direction they should avoid?

In addition to offering their critique, the experts quizzed students about the emotion the team wanted to convey, questions for visitors to think about and refining prompts for deeper storytelling. Experts appreciated how the teams embraced the complexity of the topic and offered directions on the possible next steps. Some of their comments included: “How do we make the invisible, visible?” “What else can we learn from this juxtaposition?” “How can storytelling advance the layering of narratives?”

Following the midterm, student teams addressed the specifics of their project; they refined POV statements to guide their explorations and directed their interventions. Teams assigned themselves design rules (e.g., inclusive, innovative and accessible, etc.) Also, students considered how their project could pose questions to visitors and engage them on a deeper level of reflection and possible action.?

Teams also created style guides, color palettes, expressive fonts, and logos to create a meaningful sensibility to their interventions. They created visual storyboards which helped them imagine the intervention experience through the eyes of the visitor.

Finally, prototypes were crafted that demonstrated their vision of a more equitable museum experience. This vision encompassed a wide range of inventions from analog print material to Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) technology.

Outcomes

close

close

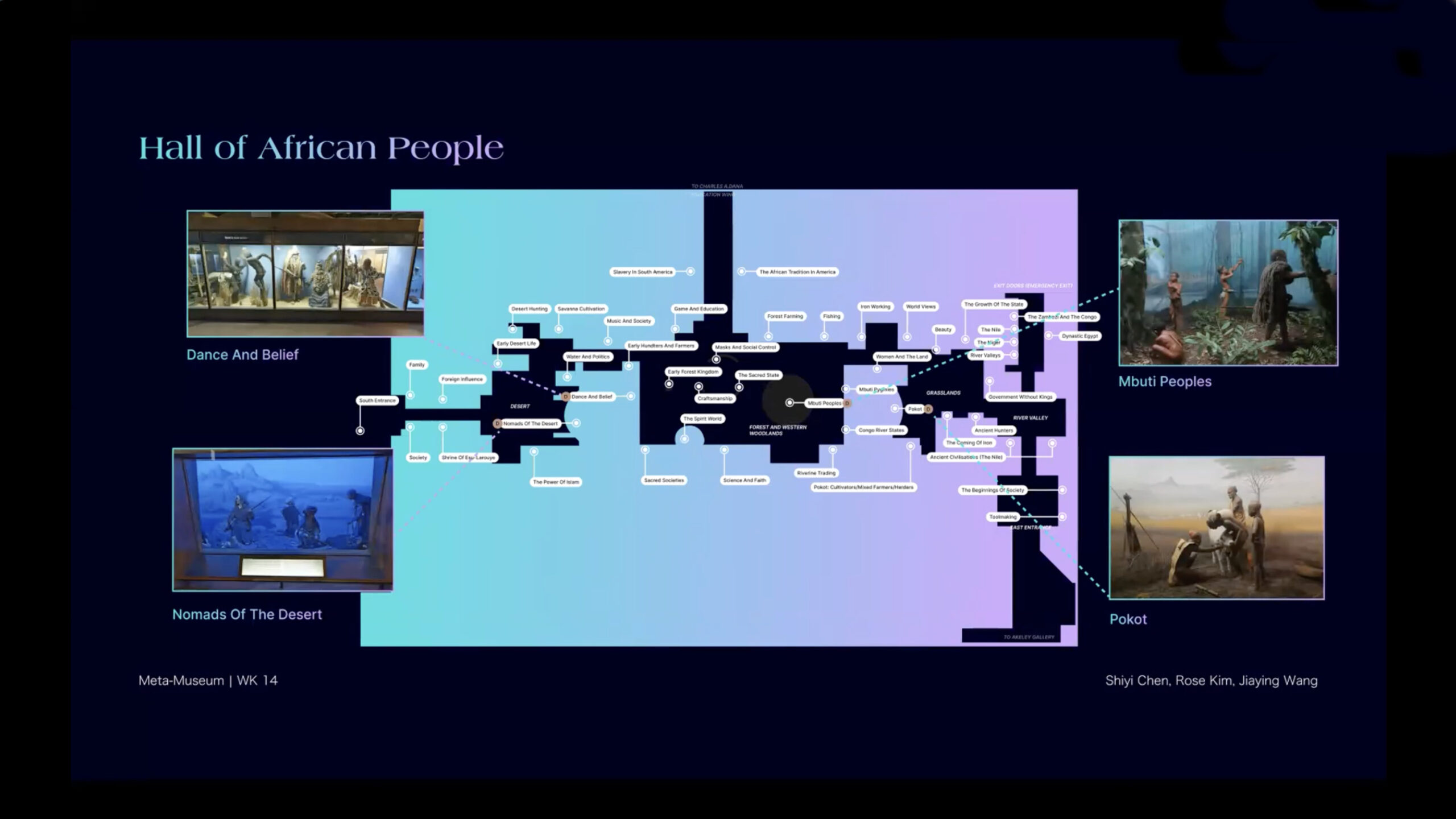

Afrotopia

Read moreShiyi Chen, Rose Kim, Jiaying Wang

This project re-imagines a large glassed diorama featuring stereotypical African nomadic people of the desert as a venue to present an alternative Afrocentric future with an intellectual narrative on how the past informs today and a future African culture.

To set the futuristic mood, the project employs colors that gradient from turquoise to purple colors.

The project has two elements. An educational component (featuring a lecture and workshop led by a variety of artists) will be tailored for different age groups from children to adults to educators. For example, a teen-centric activity would involve the classic sci-fi story, Parable of the Sower by African American writer Octavia Butler. Participants will have reading time, a mini-creative writing exercise, and then opportunities to share their thoughts/creations. After the workshop, participants can view the exhibit diorama of African nomads, similar to the nomads in Butler’s story. A docent would further describe some of the artifacts in the exhibit.

Here, participants employ the project’s second element: an app that features AR experiences. Using their phone, users scan QR codes near the exhibit and search for stickers corresponding to the artifacts; they can rearrange elements to create a new artwork/display. Participants can also add AR tags to the exhibit, answering questions such as: “What does this image make you feel?” Finally, users can view other artwork creations in a live update section.

close

close

Highlighting Religion in Africa

Read moreDominique Rivero, William Sancho, Yusheng Yang

This project creates new interactive experiences with light, sound and visuals strategically positioned around three cases that depict static artifacts and human figures representing the diversity of African religions.

Users begin the experience by referring to a wayfinding pamphlet that describes the religious diversity in Africa along with a visual map; users can also follow floor waypoints which are projected from the ceiling to reach a destination. As participants approach, sensors will illuminate the display.

Projected displays in the cases overlay the existing display. Users will be directed to examine specific symbolism of clothing, ornamentation and skin painting from various religions; descriptions will honestly communicate unknown answers and/or reasons. Videos will play current- day members of the religions featuring song, dance and other practices. Illuminated maps will show where a particular religion still exists today. Facts that have been hidden from viewers can also be highlighted.

In the example of sacred artifacts that should never have been put on public display, a case will feature a caution sign. The contents will be intentionally blurred out of respect and to honor the privacy of this belief system.

close

close

Through the Pokot Lens

Read moreHongming Li, Leeann Wei, Serafina Yu

To highlight that tradition and technology are part of the past and current African landscape, this project presents an expanded experience of a diorama of a Pokot initiation ceremony.

Two side screens and projections are added to a diorama exhibit of the Pokot people who, along with famed Pokot athlete Tegla Loroupe, will be involved in the co-creation of this expanded experience.

Underneath the diorama display, users can choose buttons that describe specific elements of the ceremony: the ox, tools, youth, etc. When a button is pushed, users will hear a short reenactment dialogue between characters. The narration will highlight the action that is being presented as well as incorporate relative information on Pokot beliefs and traditions.

The left screen will be a social media screen data visualization that will be created with the Pokot community and Loroupe. The right screen will feature a current TikTok feed from the community with lively dancing, music, and singing.

close

close

Manifest Multiplicity

Read moreYue Xi, Haoran Xu, Fanxuan Zhu

Embracing the conflicting narratives of artifacts and viewing an object’s story from multiple perspectives, this project employs a series of auditory journeys with different themes. In this instance, medical practices will be featured. Each journey incorporates various objects in the gallery hall, showcasing how different individuals – scholars, makers, collectors, etc. – would view that particular piece.

The proposed mobile app – accessible in multiple languages and with captions for those with hearing loss – will guide users through the galleries. A map on the app is displayed with different colored lines that depict the different themed journeys. Once a journey is selected, the app goes into an AR view and directs the user on which way to walk to the next object. And, objects may be included in more than one journey, allowing the visitors to understand the various ways such items were used.

Once in front of the exhibit case, users can choose which perspective they would like to hear describe the object. The app will present a short audio narrative of the object’s background, history, and use; the audio can prompt users with questions and encourage examination of certain aspects of the item. Some objects – such as musical instruments – will feature audio snips of the instruments being played. Users can swipe between perspectives of the same object.

Also, a 2-D map will be available before entering the gallery.

close

close

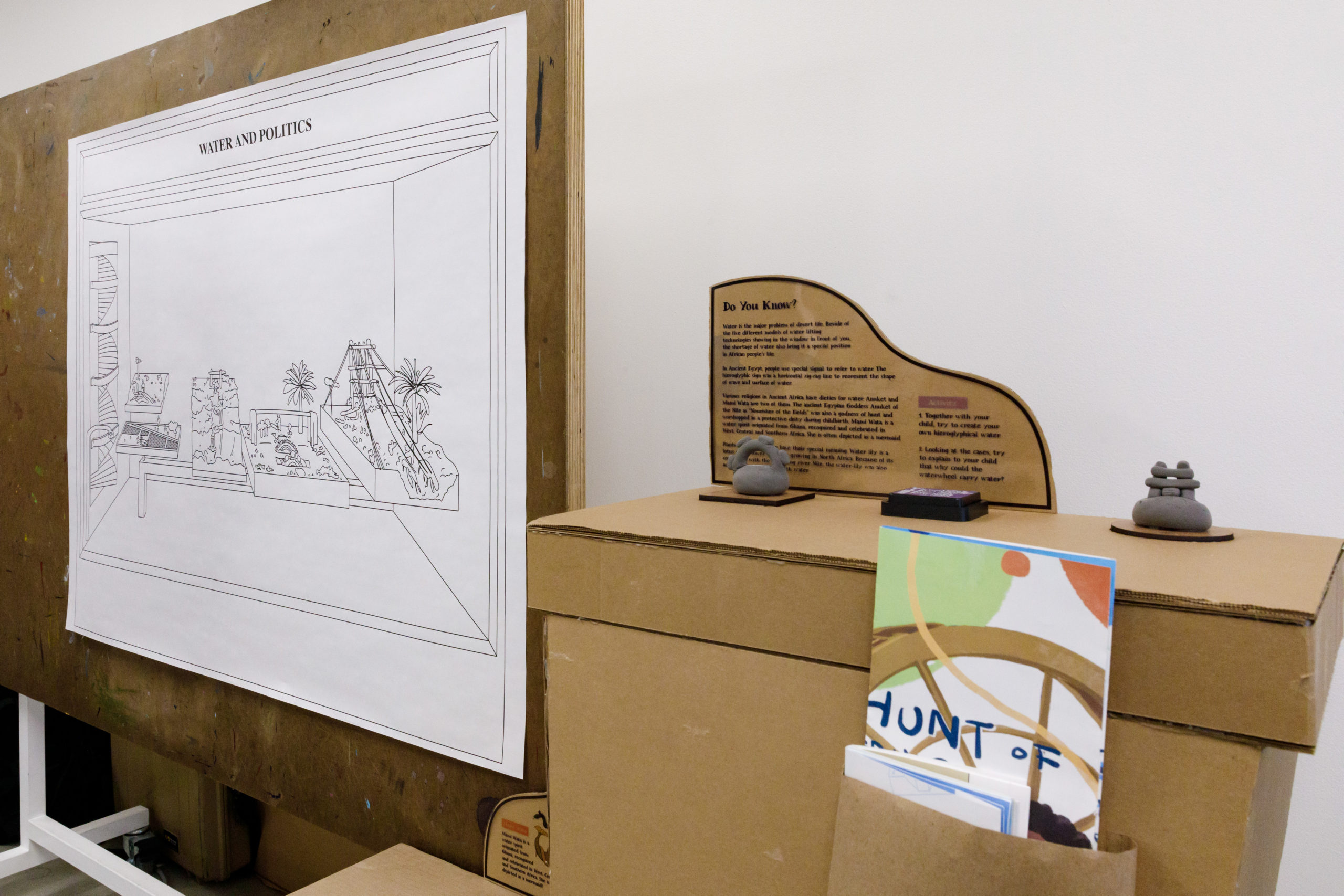

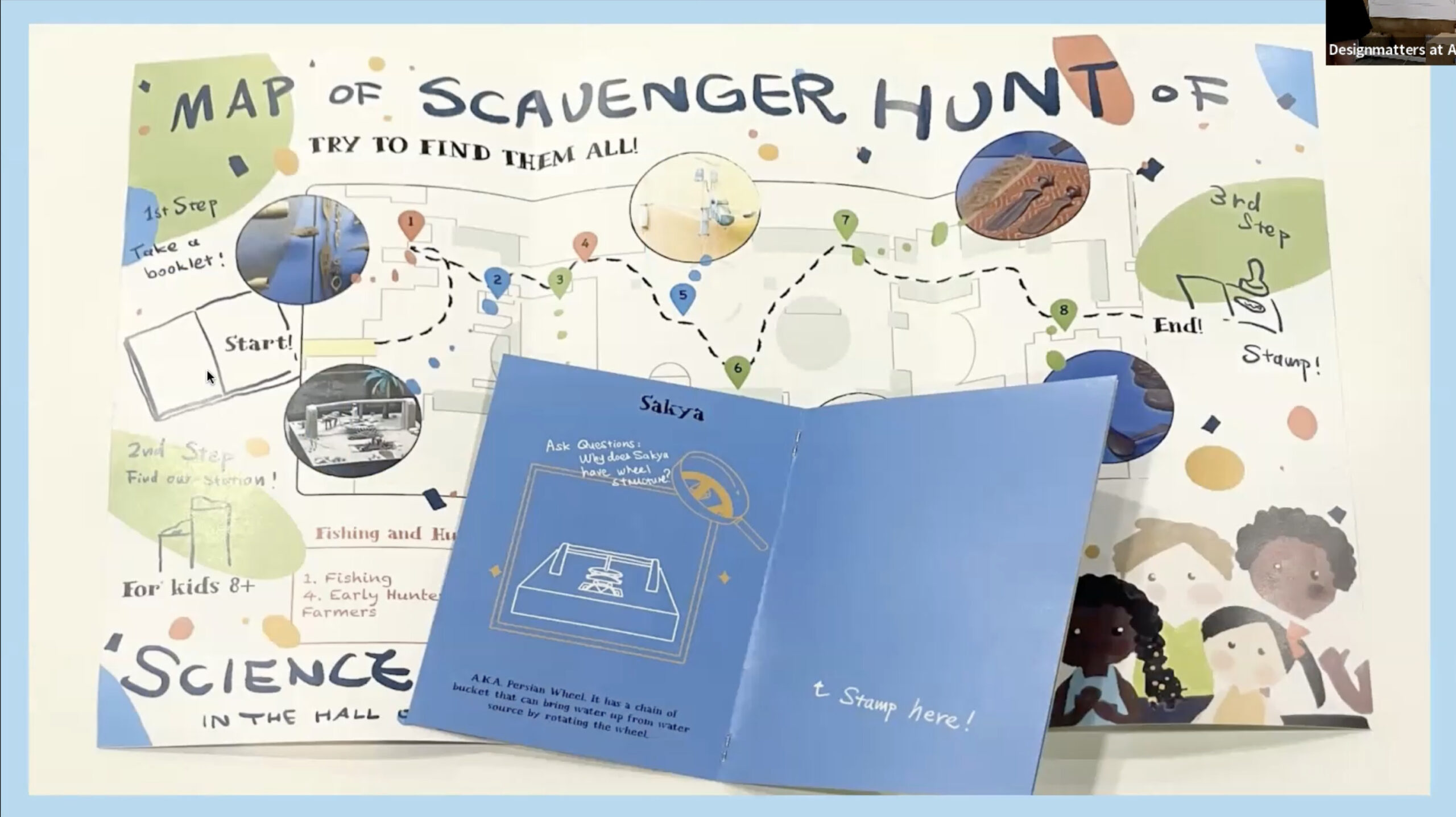

Scavenger Hunt of Science Engineering in Africa

Read moreElizabeth Costa, Yining Gao, Qianyue Yuwen

This project features how families can learn together as children collect stamps at various gallery locations for their scavenger hunt booklet. Adults and children ages 8 and older are on this educational journey as they learn the connections between ancient African practices and current global technology. Booklets and colorful guided maps are on display for pickup at the gallery entrance; kids can lead the family on the journey to the exhibits.

Once they have experienced the science/engineering facts at each display case, children and parents walk to adult and child-size podiums that are located near the exhibit. Each stand will have an extension that features text and general information based on “Did you know?” questions. The child’s stand will also feature shorter text and colorful images.

Parents will offer an inked stamp to the child who will stamp their booklet very much like a passport; the rubber stamp is returned to the adult podium stand. Each station will have its own unique stamps; stamp handles are designed to connect to engineering elements in the corresponding exhibit cases.

close

close

Stolen Pasts, Imagined Futures

Read moreDavid Espinoza Perez, Kate Ladenheim, YuningTang

Knowing that museums objects carry with them a past life and a potential for the future, this project addresses the bigger issues of colonialism and representation. Through a series of interventions, the project presents an institution that is accepting the realities of the past and is honestly educating visitors.

Large signage declaring “Not Yours to Have” and “Ours to Share” flank the entrance of galleries. Lettering is bold and poignant against a black backdrop.

For exhibit cases that contain objects obtained violently or inequitably, a set of lenticular blinds will showcase an image of the object from the past that transitions to one of an imagined future. Past imagery is represented in ghostly archival black and white; future images are hopeful representations that can be a colorful vibrant ideal, a contemporary profile, and/or other artful portraits. QR codes will provide additional information, and other audio-visual elements.

An interactive, screen-based interface will offer visitors in-depth background into some of the objects on display. Text on the case that reads “Not Yours to Judge, Ours to Evolve” followed by smaller text “Did You Know?” illuminates how some objects were co-created with African community members for specific purposes.

Display screens – about 36 inches high which make them accessible for those in wheelchairs and children – are also positioned near exhibits with additional background information and prompts for further reflection/action. Users can choose an item and select between: detailed information about the object (and its acquisition method) or a possible future vision of the object that can also include a call-to-action, such as advocate petitions and support organizations.