Adaptive Design Planning: Sea Level Rise in Long Beach Communities

- Public Policy

- Sustainable Development

In partnership with the Aquarium of the Pacific, The Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Geological Survey and the City of Long Beach, this DesignStorm challenged transdisciplinary ArtCenter students to address the impact of rising sea level on the Long Beach communities of Belmont Shore, Naples Island and the Peninsula. Students developed adaptive design planning models along with short-, medium- and long-term resilient solutions that incorporate temporary and permanent concepts to allow residents to remain in their homes as long as possible.

Design Brief

For a three-day DesignStorm experience, transdisciplinary ArtCenter students were challenged to design adaptive planning models to address the anticipated consequences of sea level rise for residents of specific Long Beach neighborhoods: Belmont Shore, Naples Island and the Peninsula, areas that contain residential properties, public recreational spaces and businesses. Students designed strategic forward-thinking concepts for the years 2030, 2050 and 2100 incorporating temporary and permanent solutions which allow residents to remain in their homes as long as possible while also planning for managed retreat.

“We put our collective heads and hearts and creativity together to help Long Beach adapt to climate change and rising sea levels. This is a huge idea and not one that many designers get to take on in their career.”

– Heidrun Mumper-Drumm, Faculty, ArtCenter College of Design

Background – Sea Level Rise

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), sea level has been rising over the past century around the world, but that rate has dramatically increased in recent decades. In 2018, global mean sea level was 3.2 inches above the 1993 average – the highest average in the satellite record (1993-present).

Overall, sea level continues to rise at a rate of about one-eighth of an inch per year.

Higher sea levels mean that deadly and destructive storm surges push farther inland than they once did, which also results in more frequent nuisance flooding. Disruptive and expensive, nuisance flooding is estimated to be from 300-percent to 900-percent more frequent within many U.S. coastal communities than it was just 50 years ago. In addition, many climate models show low-lying coastal areas will be effectively inundated, or permanently underwater, in the next century.

In the United States, almost 40 percent of the population lives in relatively high-population-density coastal areas, where sea level plays a role in flooding, shoreline erosion, and hazards from storms.

Pre-DesignStorm Research

Prior to the start of the three-day DesignStorm, students toured the Long Beach neighborhoods that will first experience the dramatic effects of rising sea level: Belmont Shore, Naples Island and the Peninsula. Students paid close attention to the physical landscape, the types of residential homes and businesses that currently occupy the sites along with the infrastructure, city-owned open spaces, parks and community buildings. They had the opportunity to meet local residents who shared personal stories.

Jerry Schubel, CEO and President of the Aquarium of the Pacific (AOP) in Long Beach offered students a series of presentations at the Aquarium about the science of climate change, methods of preparing for sea level rise currently being employed and how urban areas are adapting to new environmental challenges.

Students were encouraged to access scientific climate change reports from NOAA, the AOP, The Nature Conservancy and the Long Beach Climate Action and Adaption Plan (CAAP) to best prepare them for the DesignStorm.

“So much of my work often feels like doom and gloom with unsurmountable problems, but seeing all the ideas here gives me a lot of hope. I was really struck how quick the students could, in three days, use scientific information available from many sources and bring that together with case studies around the world to present these really innovative ideas. I was struck how formed their ideas were in such a short amount of time.”

– Alyssa Newton Mann, Coastal Project Director, The Nature Conservancy

Day One

Student Icebreaking Prompt, Empathetic Role-Playing, Team Ideation

The DesignStorm kicked-off with students displaying their field trip observations; these visual representations connected stakeholders who will be affected by rising sea level and included homeowners, government officials, tourists, companies, and more.

A formal welcome introduced the faculty (Heidrun Mumper-Drumm, Gerardo Herrera and Mariana Prieto) and stakeholders who would also have an active presence for the DesignStorm: Jerry Schubel, President and CEO of the Aquarium of the Pacific; Alyssa Newton Mann, Coastal Project Director at The Nature Conservancy; and Bob Grove, ArtCenter faculty member and Aquarium docent.

Through engaging hand-drawn illustrations by Teaching Assistant Lovisa Lund, white boards surrounding the classroom preserved and presented notes, class activities and key concepts that teams could quickly reference throughout the entire DesignStorm.

The students introduced themselves via an icebreaking prompt, an exercise that also fueled discussion on critical concepts about the nature of resiliency. One by one, students described a personal story answering the question, “When did you find that you had to adapt to a situation that changed? How and what did you do?”

Individual accounts of challenges, surprises and unexpected happenings dovetailed into bigger lessons about planning for emergencies and methods of adaptation. Some students from Pacific/Asian countries related personal accounts of how flooding has affected their homelands and hometowns.

Students discussed how transitional adjustments can be created and accepted when situations radically change and normal isn’t normal anymore. Conversations stressed the importance of understanding the difference between adaption vs. reaction, the resiliency of youth, and methods to move people and projects into action especially if imminent danger isn’t directly obvious.

Two presentations followed which offered students even more resources and information to use during their ideation.

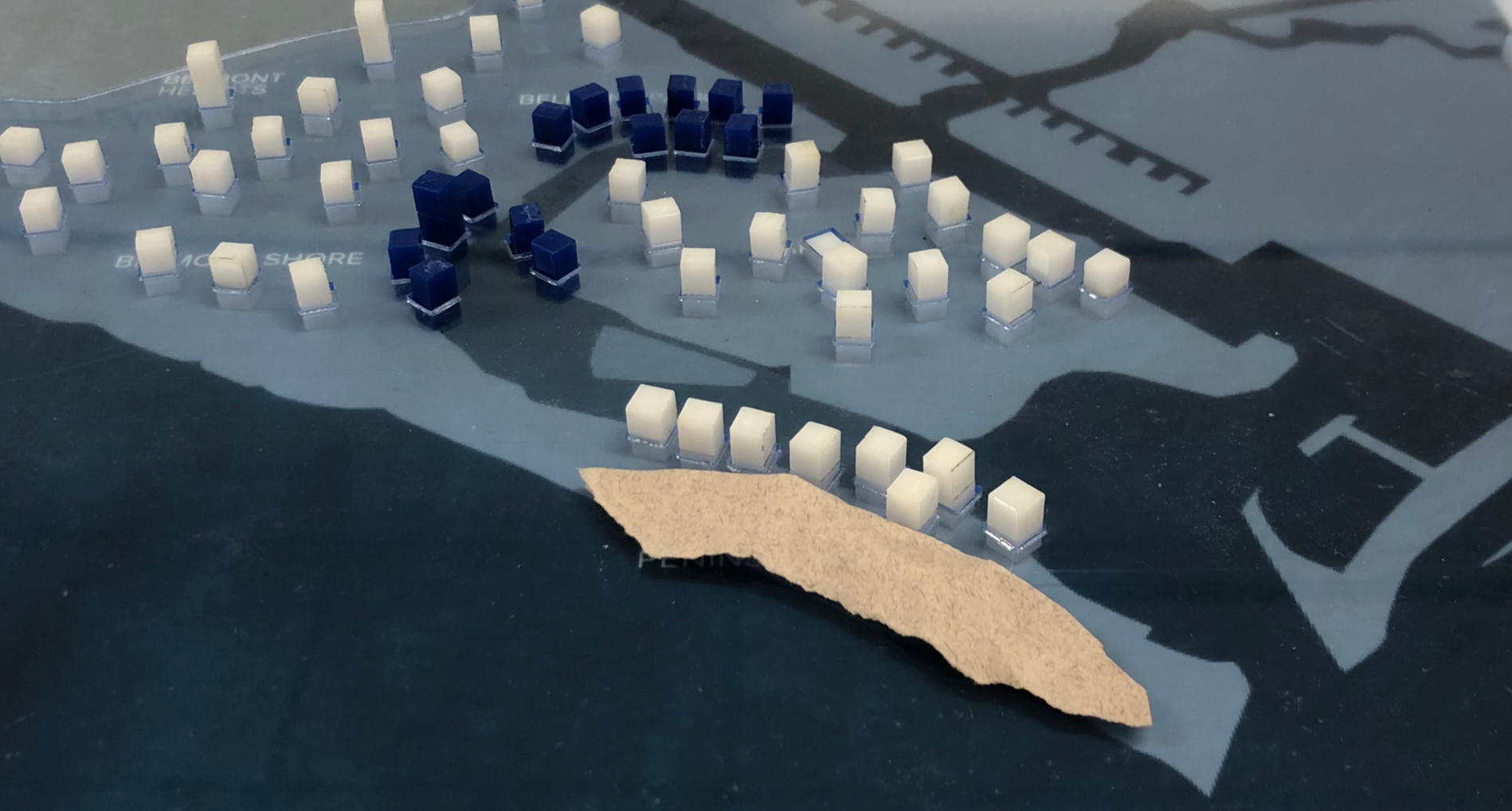

Julian Calil, CEO and Co-Founder of Virtual Planet Tech that translates imagery into 3-D representations, presented specific realistic aerial views of the Long Beach neighborhoods that are part of the DesignStorm focus. Calil explained the process of marrying the photographic images with 3D models and data from USGS to create the images and forecast future possibilities. Additionally, this technology can take into account how certain strategies – i.e. sea walls, sand dunes – can mitigate and/or reduce the effects of rising sea level.

A presentation by Mann from The Nature Conservancy provided a general overview of the hazards of climate change along with nature-based solutions that have been proven effective. Mann described impending disasters as increased flooding, wildfires and more as climate change progresses, especially when it comes to coastal habitat. She outlined ways that the Conservancy is advocating for resiliency as coastlines disappear and shorelines are submerged. Additionally, Mann presented ways her organization is communicating and educating the public about the realities of sea level rise, offering methods for “managed retreats” in order to reduce risks, relocate strategically and effectively use natural solutions.

Mann explained how seawalls have historically been used in California; today more than 10 percent of the entire coastline is propped up by such reinforcements. Sand from pounding waves can eventually “scour” and erode seawalls. Better solutions for combatting the rising waves include: planting oyster reefs, revitalizing coastal marshlands and creating vegetative dunes.

Empathy Exercise – Seeing Through Other Eyes

As they digested all the presentation information, students engaged in an exercise of role-playing Long Beach stakeholders who will be affected by rising sea level.

In small groups, students assumed various identities: a longtime resident, Coastal Commissioner, city official, contractor, etc. At each table, a guest would play themselves (Mann: Nature Conservancy, Schubel: Aquarium of the Pacific, etc.). Groups were given appropriate funds and policy options. The goal was to prioritize policy through negotiation and have everyone leave the table with a “sense of hope.”

In character, students argued, compromised, reflected and determined which policies to support with their assets. They debated the pros and cons, discovered the ramifications of their actions on certain groups and looked at worst case scenarios.

Prizes were given to the group who achieved the task in record time.

After the exercise, the class discussed the surprises and frustrations of working with individuals who have a diverse set of goals and aspirations. They realized that certain groups tend to compromise more than others; while other groups are traditionally more vulnerable to change. Of the numerous insights gleamed from the exercise, the students concluded that having to consider multiple points of view can be overwhelming, but necessary.

Discussion, Ideation and Preliminary Presentation

During a working lunch, students had the opportunity to don a set of Virtual Planet Tech goggles to experience a VR simulation of sea level rise.

In the afternoon, students brainstormed “What if…” concepts, highly aspirational Blue Sky ideas that could inspire down-to-earth solutions. Among the possibilities, students ideated about co-existing with water, how communities could be created around flood waters, and how floating cities could one day the norm.

From the hundreds of potential concepts, students clustered like-ideas together and viewed the solution from practical applications of how it addresses inequalities, responds to new risks, changes behavior, protects the ecosystem and improves infrastructure.

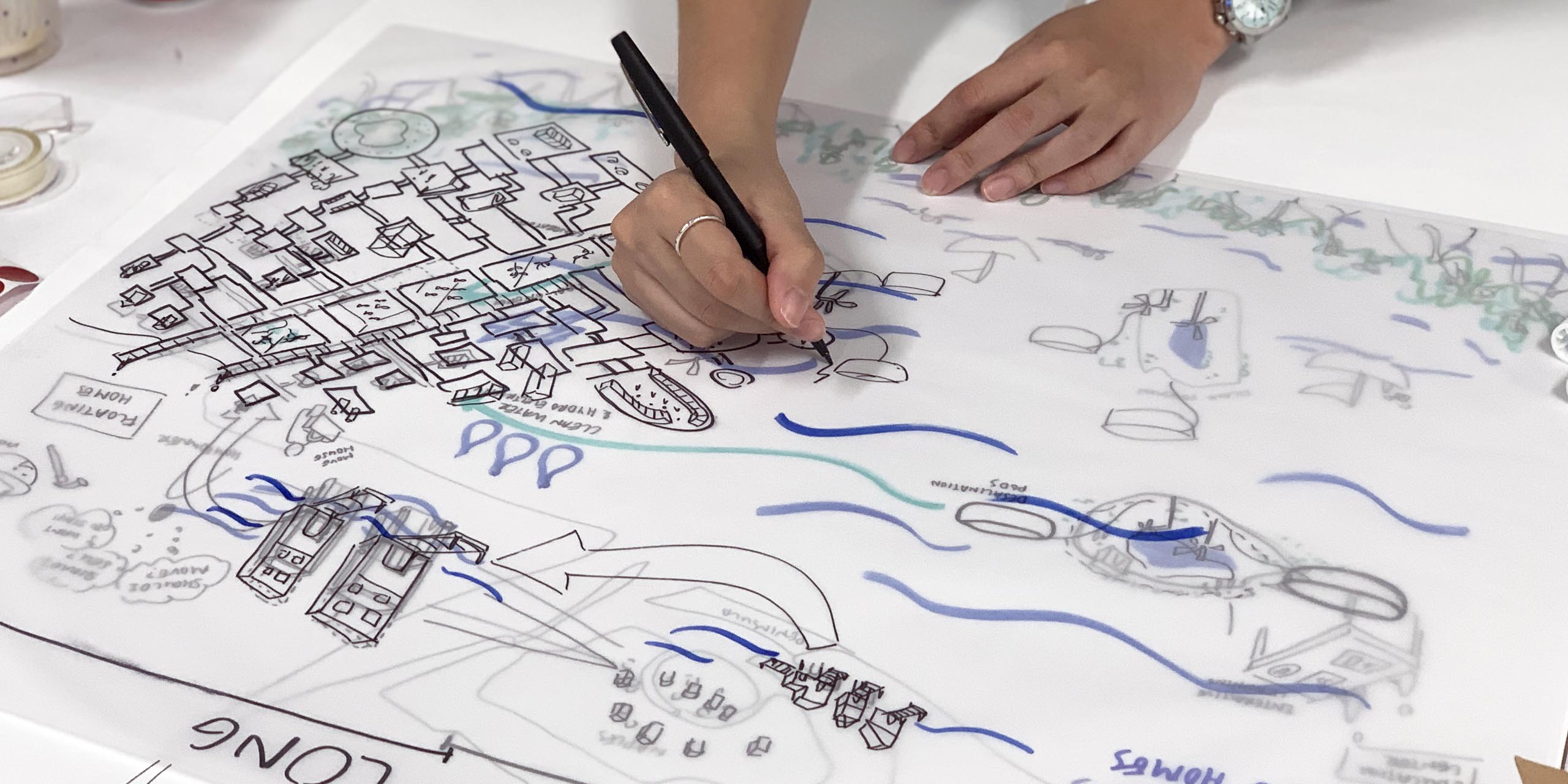

Students were divided into three-member teams and were instructed to present three preliminary directions to investigate for their final solution. With the clock ticking, they sketched out concepts, created storyboards, referred to scientific research and fleshed out possibilities to make a presentation at the end of the day.

Even with less than a few hours of preparation, student teams presented their initial concepts to an audience, explaining the science supporting their design thinking and outlining the best methods to implement their ideas. Audience members offered thoughtful and encouraging feedback, often suggesting which ideas seemed to have the most merit and possibilities.

At the end of the day, teams regrouped, distilled their ideas by combining concepts and eliminating others. They divvied up duties moving forward to the next day.

“I really enjoyed spending time applying all the technical learning and training I’ve received in other studio classes to a real-world issue. This project has serious and actual implications; getting the chance to work with people in legitimate institutions on a big real topic was so worth it.”

– Cullen Townsend, Student, Illustration

Day Two

Research/Ideation, Journey Map, Reimagined Presentation

After a brief recap of the events of Day One, students were given more specific parameters for their projects: concentrate on three time benchmarks (the years 2030, 2050 and 2100) as it relates to the three Long Beach communities. Additionally, teams should use the projected sea level rise of 1 foot (2030), 2 feet (2050) and 6 feet (2100).The overall goal is to keep the residents in their Long Beach homes as long as possible and to create a plan for a managed retreat once residents are no longer able to remain in their homes.

Instructors also directed students to build upon their ideas noting how resilient they are in the face of climate change and how their design directly affects the user (i.e. residents of these three communities). Adaptation strategies could have multiple rewards; improving the infrastructure could simultaneously protect ecosystems and provide long-term benefits to the neighborhoods. Overall, the design phases need to have a direct communication plan which keeps all shareholders (residents, tourists, civic leaders, etc.) in the loop.

Students delved deeper into their concepts when they created a Journey Map outlining how/when residents will move, what will happen physically to the neighborhoods and how to employ nature-based deterrents to slow down the effects of rising sea level. Their design needed to address specific groups, evoke an emotional reaction and present a time perspective as well as how they envision strategic communication phases.

Throughout the rest of the morning and early afternoon, student teams worked quickly but thoughtfully on their presentations. Students assigned duties, re-wrote, created drawings and practiced their pitch. Students developed their digital presentation as well as creating props and physical accessories that would help tell the story of their concept.

By mid-afternoon, in front of DesignStorm partners, teams presented their refined concepts, explaining their vision for the Long Beach communities and outlining methods that will hit those three benchmark dates. Since this was the last critique session before the final presentation, feedback was detailed and offered specific elements that could make their projects more attractive, sustainable and streamlined.

“This is the first time I’ve experienced a DesignStorm. I was instantly amazed and how well the instructors all worked together and were so positive and encouraging to the students. Their enthusiasm shifted down to the students. The whole room was on a positive plateau; just look around at the hundreds and hundreds of sticky notes. I was excited to see these initial ideas, refined and then presented at the final.”

– Bob Grove, ArtCenter faculty and Aquarium of the Pacific docent

Day Three

Preparation, Presentation, Debriefing

The final day began with students entering the classroom which was now an active design workshop filled with models, 3D representations, mapping, and small prototypes of structures. Teams had a few hours to hone their ideas and put on the finishing touches.

Teams referred to their notes, Post-it ideas, white boards and conceptual revisions to create a step-by-step visual storyboard depiction of how communities would implement, use and benefit from their concept.

As teams transformed their ideas into graphic 2D and 3D representations, instructors stopped by to question choices, challenge their thinking and offer practical structural advice.

In the afternoon, the room was prepared for the visitors. Once they arrived, guests – which also included Long Beach city planners, Aquarium and Nature Conservancy staff members – were given an overview of the DesignStorm challenge before the final presentations.

“This is a challenge that is too big for any one person to take on, or any one government to take on. The students got to see and feel the power of collaboration. Those big broad visions can sometimes feel out of reach…but they don’t have to be. The students were amazing. I hope they know that there is no challenge that’s too big to try, but instead ask, ‘OK, what can we do?’”

– Mariana Prieto, Faculty, ArtCenter College of Design

Project Outcomes

close

close

H2O Home

Read moreHelene Huang, Pitchamon Karnchanapimolkul, Lilibeth Mendez

Long Beach residents will temporary locate to high rise towers constructed in a nearby neighborhood, but will be able to return to their original neighborhoods which will be a community of floating amphibious houses.

In 2030, a communications campaign will alert residents about the upcoming move; the Peninsula residents will be the first group to relocate, followed by neighborhoods in clusters. An Aquarium of the Pacific exhibit will outline plan details: the futuristic amphibious houses; “Sea Street,” the new floating business/market sector; the new aqua farming endeavor; an underwater park at the oil islands; and how the shoreline’s ecosystem will change. The high rise community towers start construction.

In 2050, outreach continues with positive messaging. A few amphibious homes will be available in small pad-like configurations. Visitors/residents can use their own boat – or a water taxi – to shop and dine at “Sea Street” a floating business district that is moored to the area using concrete pillars over the aqua-farming areas. Other shops are floating markets and travel to customers. Off the coastline, the oil islands will transform into underwater parks with overhead domes.

In 2100, residents return to their old neighborhood and move into a community of amphibious homes connected to each other on floating platforms. The now empty high rise towers now can be offered as affordable inclusive housing. The Peninsula’s seaside will be transformed into a series of natural sand dunes which will naturally slow the eroding effect of waves.

close

close

Tidepool Terrace

Read moreBrittanie Gaja, Anyoung Roh, Amanda Sutanto

Tidepool Terrace will create a living sea wall in the current community of the Peninsula that will provide a sturdy protective infrastructure also restores lost habitats and creates community through interactive and educational public spaces.

The flexible nature of the sloping terrace wall heightens as the sea level rises and will feature native planting vegetation and a boardwalk on top. The structure will reduce the destructive power of the waves and encourage rich tide pool ecosystems to form on former sandy beaches.

In 2030, residents will be educated about their upcoming move; their demolished homes will provide materials for the foundation of the seawall. Drainage and permeable pavements will be created in Belmont Shore and Naples in preparation for the approaching waters.

In 2050, residents will be rehomed in a series of temporary floating houses while the Peninsula is being restored to a more natural estuary. Nearby, terraces will be created on the sea wall.

In 2100, residents will be welcomed back to the area to inhabit homes, constructed with recycled materials, which are affixed below the water on platforms. Visitors and residents take in the views from the boardwalk on top of the sea wall and can also explore the rocky nearby tide pools.

close

close

Stay Connected

Read moreAnya Radzevych, Veilinda Rusli, Amanda Wallgren

Long Beach residents who have to relocate are able to be emotionally and economically connected to the shoreline through a restored natural habitat and investing in an underwater aquaculture farm.

In 2030, a kelp farm will be initially installed along the oil islands which eventually will provide local jobs. Residents will be informed about the upcoming relocation and benefits program. Experience Park, located north of Belmont Shore, will be environmentally restored with native vegetation blocking winds, gray sand to slow erosion and coastal plants that fortify the shoreline. Through AR and VR technology, visitors will be educated about how the landscape will change because of sea level rise. At night, guests can experience a light projection display on the rocks.

In 2050, the kelp farm will expand with multi-tropic aquaculture opportunities and residents who have been displaced will receive stock in the growing company. Experience Park will expand (similar to the Highline in New York City) with walking paths that extend out to the water. Oil islands will be repurposed as wind energy

In 2100, Experience Park will be a major center for tourism as well as a community center for residents; boats will be able to access and dock nearby. An underwater glass pavilion gives visitors views into the local farming aquaculture. Locals will continue to generate passive income from the nearby farming endeavors.

close

close

Peninsula Project: Adapting to Rise in Sea Level

Read moreMichelle Affandy, Derling Chen, Rose Zhang

This concept builds up and out using natural protection from rising sea waters, as well as using old structures as foundational elements. This phased project employs a careful timeline of happenings that will move residents away from the area for restoration and then bring them back.

In 2030, a kelp forest and oyster habitat will be installed off the shoreline; the offshore oil islands will transition into a water desalinization facility. Residents will be presented with options to move or stay.

In 2050, oil islands will be underwater but will be the foundational support for the desalinization pods. Residents will move to temporary structures as their old homes will be retrofitted and built upward in anticipation of the rising waters. While homes are being refurbished, residents can relocate to temporary floating homes which will serve as a base for future floating communities. These modular communities will receive power and water from the desalinization pods.

In 2100, floating home communities will expand and incorporate businesses. Residents will be back in their original (and retrofitted) homes. Submerged oil islands will continue to support the desalination pods that will provide power and water to the local residents. The aquaculture farming from the oyster beds will contribute to the local economy and provide food.

close

close

Otter Homes

Read moreBrandon Camino, Seohyeon Lee, Cullen Townsend

Through dramatic visible demonstrations, residents will see the impact rising sea level in their community, and will systematically be relocated while new coastal housing is being constructed: a re-imagined micro beach bungalow, aka “otter home” and floating villas.

In 2030, the City will start a dialogue with residents about the upcoming relocation and housing options. Public work projects will be constructed in well-used parks, open spaces, city-owned parking lots, etc. Created first as sunken basketball courts, these spaces, when flooded, are a visual and dramatic reminder about the reality of sea level rise. As a temporary drainage, these spaces will also be a holding facility until waters can be pumped back into sea. Other locations are targeted for wetlands restoration projects. Floating villas start construction.

In 2050, residents are moved into sustainable compact “otter” homes that can be placed on land or water or be mobile. Land otter home sites are targeted on open spaces and vacant properties outside of the three affected communities but only minutes away from the water. Floating otter bungalows will be established around Naples Island in Alamitos Bay; residents will be moved in systematically. These floating structures can be temporary or permanent.

In 2100, floating villas welcome residents back to their original properties; their compact size is more environmentally sustainable and offers residents a deeper sense of community and oceanfront view. Multi-leveled villas are positioned in the center of a pod of floating otter homes connected by platforms. Residents can dock their boats in assigned water spaces.

“Sea level rise is a global problem that is going to continue well beyond this century. It’s a global problem that’s not going away. We have to have some case studies where people have co-existed successfully and maintained their communities – and Long Beach is a good place to imagine and embrace the possibilities. It’s a good laboratory. With a population a little less than half a million, its small enough to be manageable but it’s large enough to capture national and international attention.”

– Jerry Schubel, President and CEO of Aquarium of the Pacific

Next Steps

Students and faculty presented concepts to stakeholders in Long Beach in February 2020, with hopes of engaging partners for a follow up studio later in 2020.